CRAW Region #2, Country #8: Colombia

If you think the countries of Central America had some fascinating origins, you haven’t heard anything yet! The land that makes up present day Colombia has been there and back… Literally.

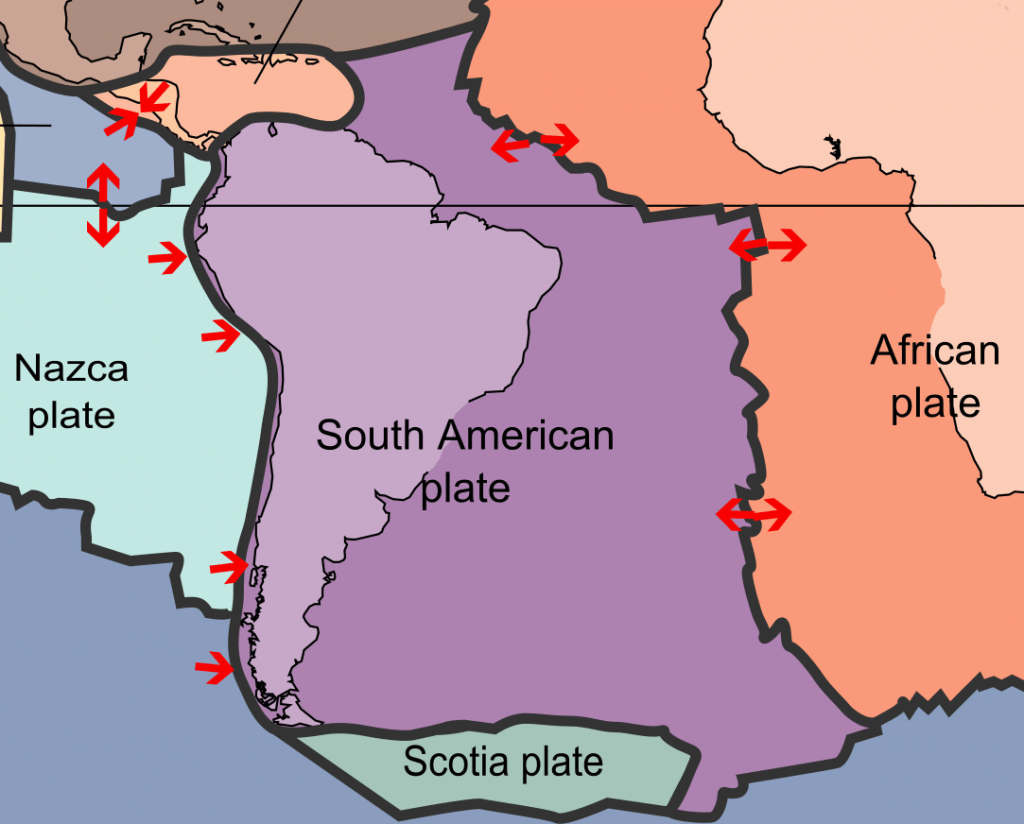

The first thing you have to do is to eliminate the idea that there is such a thing as solid ground. We all learned about the different parts of the earth; the crust, the mantle, and the core, which creates an image of an earth with a single hardened layer encompassing it. But that is not anything close to a true image. Picture instead, the continents as massive slabs of land floating about on the mantle like so many ice floes. They crash, and grind, and carom off one another like bumper cars. These collisions raise mountain chains and tear entire continents in half.

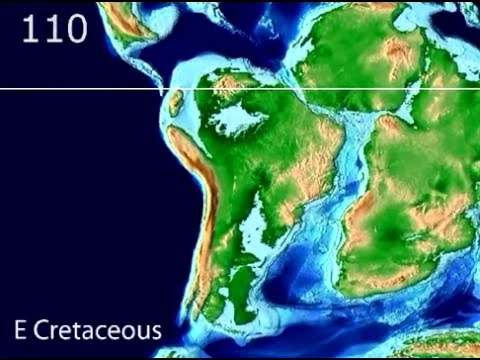

160 million years ago , a lot longer than it sounds, all of the continents had run together to form one huge supercontinent.

The east side of South America and the west side of Africa at the equator were fairly welded together, with one of the great mountain chains of all time straddling the seam between them. North America sat squarely on top of South America, and was wedged up against the Western side of the top half of Africa. Even today it does not take a jigsaw puzzle master to see where South America once fit into Africa. On the west side of South America, Colombia was just offshore, part of the continental land mass, but under water. North America was in the process of breaking loose and starting its drift to the west, and as it came loose it sort of pivoted around the center. The top part headed west and the bottom part (what is today the Caribbean Plate) swung east and slammed into the corner of South America that is now Colombia.

Let me break away here to explain that the Andes Mountain chain splits into three separate ridges of mountains north of the Ecuador-Colombia line. The easternmost is called the Oriental Andes. It curves eastward all the way to the Venezuela border, where it makes almost a right angle turn to the north and goes on to the Caribbean Coast.

Picture the North American Continent making a partial spin counterclockwise as it slides to the east, and as it turns, that arm of the Caribbean bangs into the top corner of South America and pushes up a line of mountains .As it continues to pivot around the centerpoint that bottom corner of North America is moving east, even as the total mass of the continent is moving west, and it pushes the top half of that ridge of mountains it has created eastward, bending it… until it is suddenly yanked away by the rest of the continent, leaving the last part of the mountain ridge still pointing north…. Except hundreds of kilometers east of the bottom half, with the part bent eastward connecting the north pointing ends.

At 150 million years ago, South America began to split off from Africa at the bottom. Who knows why?

Maybe it was just ricocheting from the collision that welded them together to start with. Maybe the torque from the shot North America landed at the top caused the split to start at the bottom. Maybe it was just responding to mysterious currents in the mantle on which the continents float. Whatever drove it, by 100 million years ago South America had separated completely and was drifting west in pursuit of North America.

About 70 million years ago South America caught up to the Caribbean extension, and smacked into it again. This time it pushed up the second of the Andean Cordilleros in Colombia, the Central Andes.

Did that collision break off the Caribbean Plate from North America? I don’t know. But, by 50 million years ago the Caribbean plate was plowing southwest, bulldozing up the ridge of material that formed into Central America in front of it. The Caribbean Plate was being driven south by North America and west by South America, so that ridge formed a line from the northwest to the southeast extending from the bottom of North America. 40 million years ago that same battered side of Colombia rammed into the tip of Central America, pushing up the western range of the Colombian Andes, the Occidental. Now, look again at the map again with this collision in mind, and suddenly that S shape of Panama makes sense. The formerly straight ridge of Central America is bowing under the force of the impact with South America. And the formerly submerged land mass of Colombia has been shoved high into the air by the force of the side impact with the small, hard Panama Plate, which refuses to slide underneath the South American Plate. Colombia’s ring of volcanic and earthquake activity form an arc around this impact zone.

What we see today is not the end result of these of violent collisions, but rather a freeze frame picture of collisions in progress.

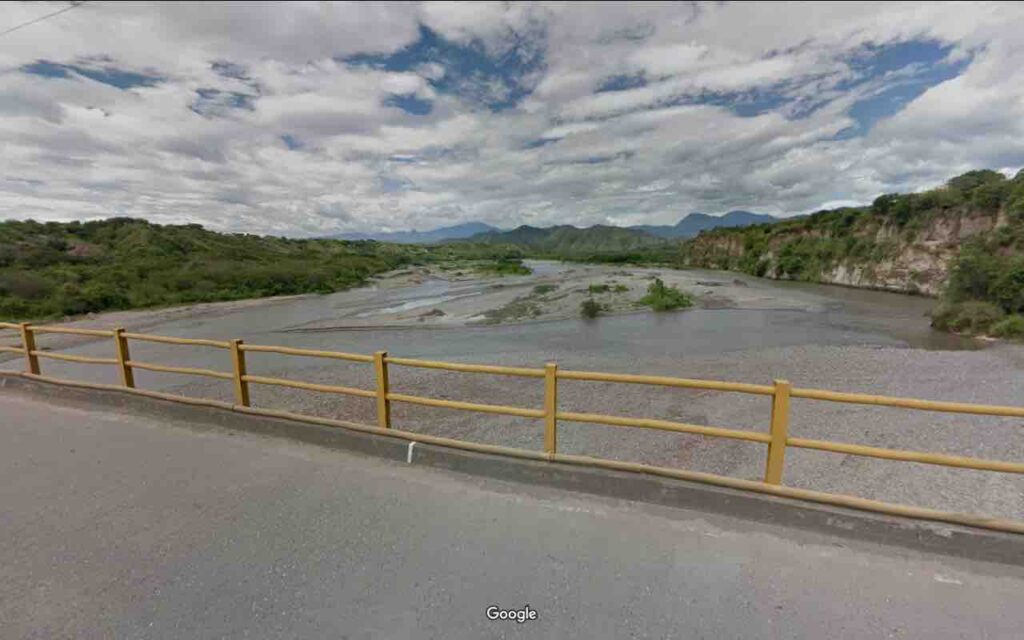

Between the Oriental and Central Andes is a wide high valley, drained by the Magdalena River. The much narrower valley between the Central and Oriental Andes is drained by the Cauca. Those two rivers join on the Caribbean Coastal Plain., and in those three regions reside most of the population of today’s Colombia.

It is obvious that the dispersal of the First People into South America had to pass through Colombia. The earliest traces of human presence date back some 20,000 years. By 14,000 years ago there were nomadic bands occupying the region and carrying on trade with other peoples. Between 7,000 and 3,000 years ago they made the transition to agrarian societies with permanent settlements.

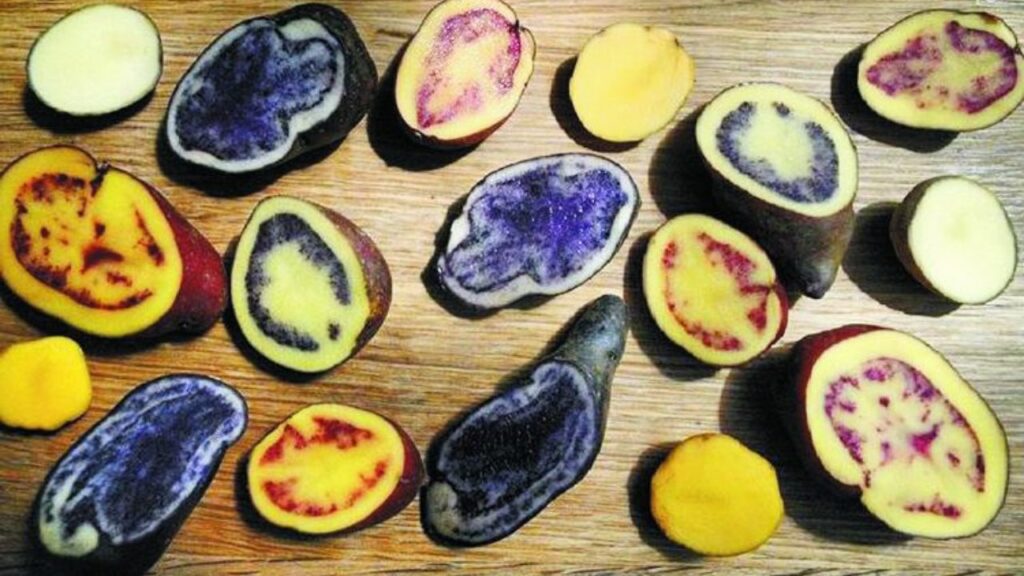

In the vertical world of the Colombian Andes, the primary crops were defined by location: Yucca (Cassava) at the lower elevations, corn at the middle elevations, and potatoes in the high country.

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the inhabitants of Colombia were Arawak, Carib and Chibcha and closely related to the inhabitants of Panama and the Caribbean. There never developed in this region the great civilizations like the Mesoamerican to the north, or the Andean to the south. At the time of the Spanish arrival, the Muisca Confederation, the Tairona Cheifdoms, and the Quimbaya civilization were the strongest native political units to stand in their way.

And those did not stand for long.

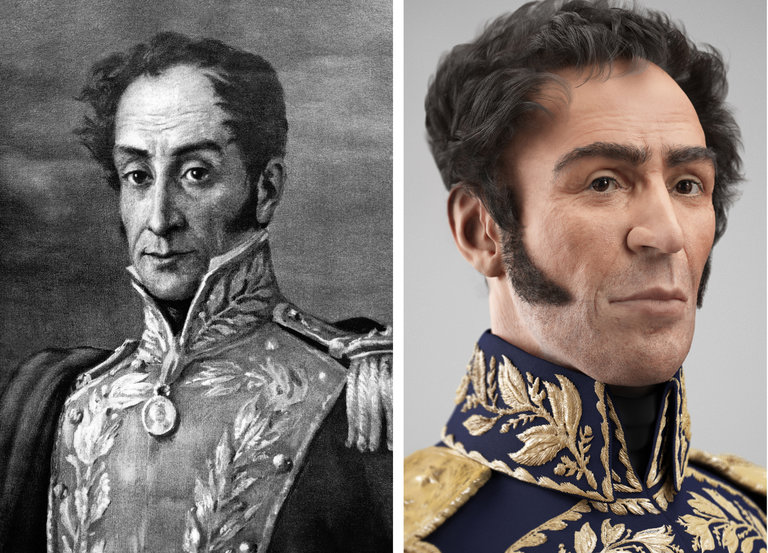

Under the Spanish, Colombia was the center of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, today’s Panama, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. When the Spanish Empire dissolved in 1821, it became the center of the Republic of Columbia known in the history books as Gran Colombia, which included the Spanish parts of Region 2.

Brazil was occupied by Portugal). The Republic of Colombia itself had fragmented by 1830, and Colombia (with Panama) became the Republic of New Granada. The government of the new country morphed through several forms becoming in turn: the Granadine Confederation (1858) and the United States of Colombia (1863) before reviving the name Republic of Colombia in 1868 (leading historians to create the name Gran Colombia to differentiate the current Republic from the original). Panama seceded with US assistance in 1903 when Colombia refused to sell the rights to build the Panama Canal to the US.

With its strong regional identities, Colombia has faced some sort of ongoing revolution since the 1960s. Starting in the 1980’s the Drug Cartels added a third player to the competition for control of the country. At the current time, Colombian violence is at something of low ebb, and it is mostly safer than Mexico. You won’t have to worry much about being kidnapped or caught up in a gun battle until you reach Cali on the approach to Ecuador.

After you deplane on the beach at Arboletes, you begin your trip across Colombia by asking a local for directions to the nearest place to get your Passport stamped.

Since the ferry from Colon has terminated operations, it is no longer certain that there will be an office in Arboletes. Until you get that stamp you will be in Colombia illegally, which is not the best idea. The course first runs just inland from the beach for about 5 kilometers to Puerto Rey, and then turns inland to reach Los Cordobas at 10 kilometers. If there was no office in Arboletes, you should be able to attend to your Passport stamp in Los Cordobas.

Turning inland, you will be crossing the Coastal Plain of the Caribbean

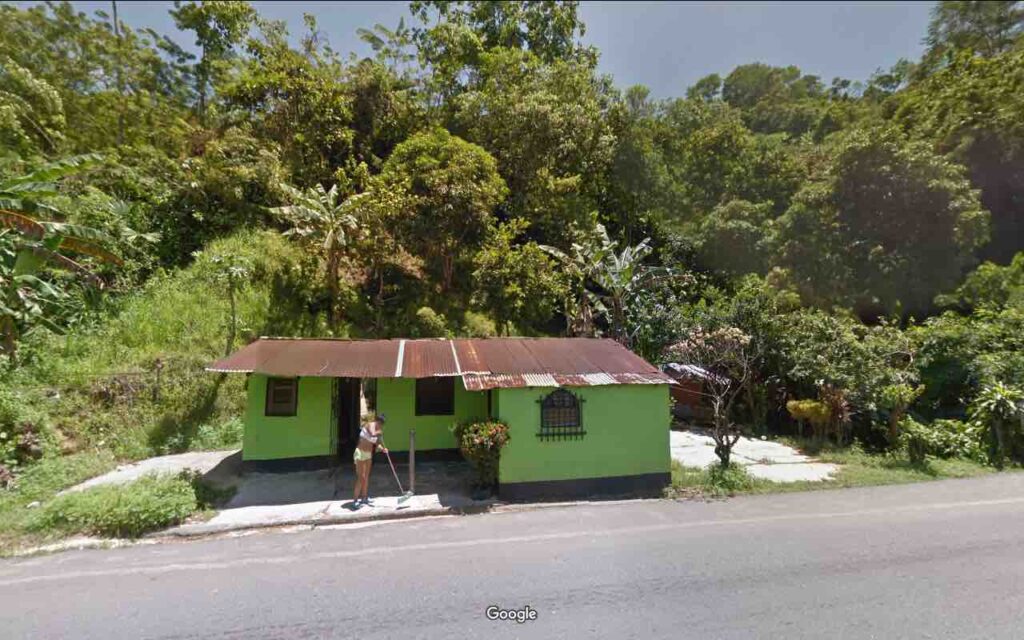

Along the tree lined road you will pass numerous small farms, with quaint wood and stucco houses, surrounded by their crops of bananas, oil palm, tropical fruits, and maybe coffee or cotton.

You can stop at a small tienda to lunch on arepa, a sort of cornbread, spread with diablito. Just be sure never to say that arepa is Venezuelan!

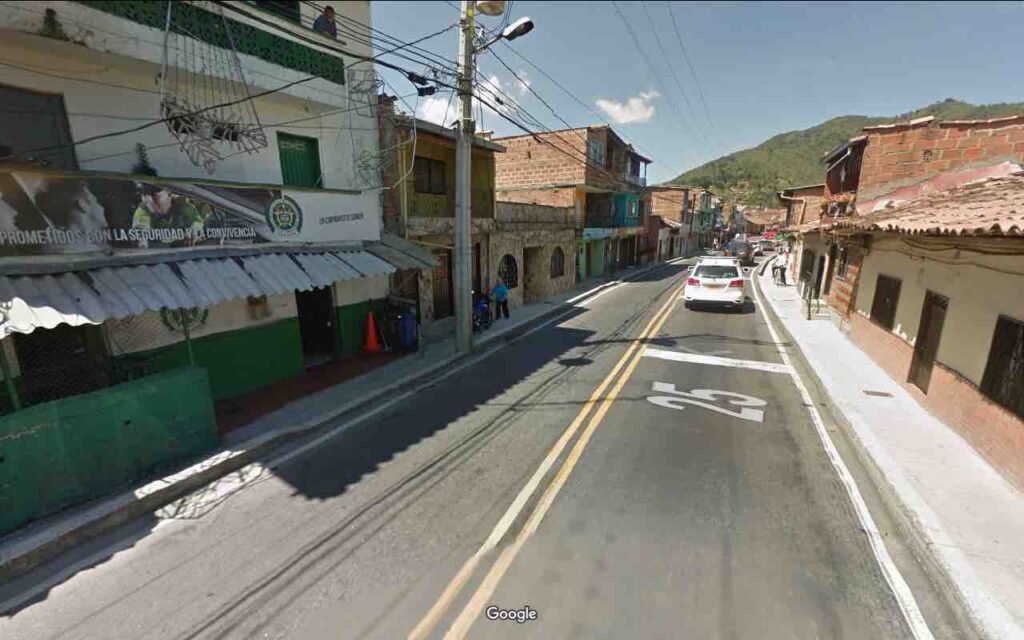

About 70 kilometers in you will pass thru the city of Monteria (Colombia 22) and cross the Rio Sinu. After you leave Monteria, it is more of the peaceful countryside. The number of cattle ranches increases as you work your way inland, but the intriguing shortcuts, small houses and delightful small shops and restaurante will make it difficult to hurry thru this part of Colombia. (Colombia 24) Numerous small villages dot the route making this part of the journey almost seem like an adventure in a different world.

I guess for those of us who do not live in South America, it is a different world.

By 200 kilometers you are starting to climb into the hills. You soon will realize these are not just hills, as you make a grinding climb up to 10,000 feet as you enter the Oriental Andes.

The climb will be rewarded by endless scenic vistas.

Between 250 kilometers and 450 kilometers it is serious mountain running, huge climbs and descents, until you finally drop down into the Rio Medellin branch of the Rio Magdalena basin. The Medellin Valley is a place of rolling hills and lush pastures, against a backdrop of mountains.

At 470 kilometers you will enter the outskirts of the famed city of Medellin.

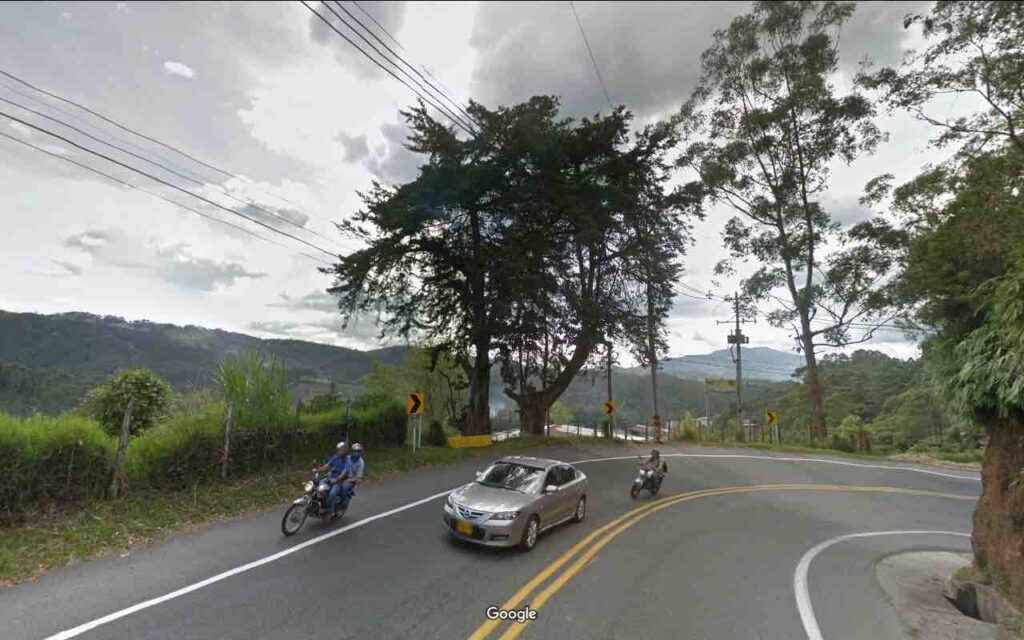

You will make your way though teeming neighborhoods down to the center of town, where you will make a right turn and run alongside the Rio Medellin to Itagui at 500 kilometers and then commence another backbreaking climb into the mountains… this time on a narrow road teeming with vehicles.

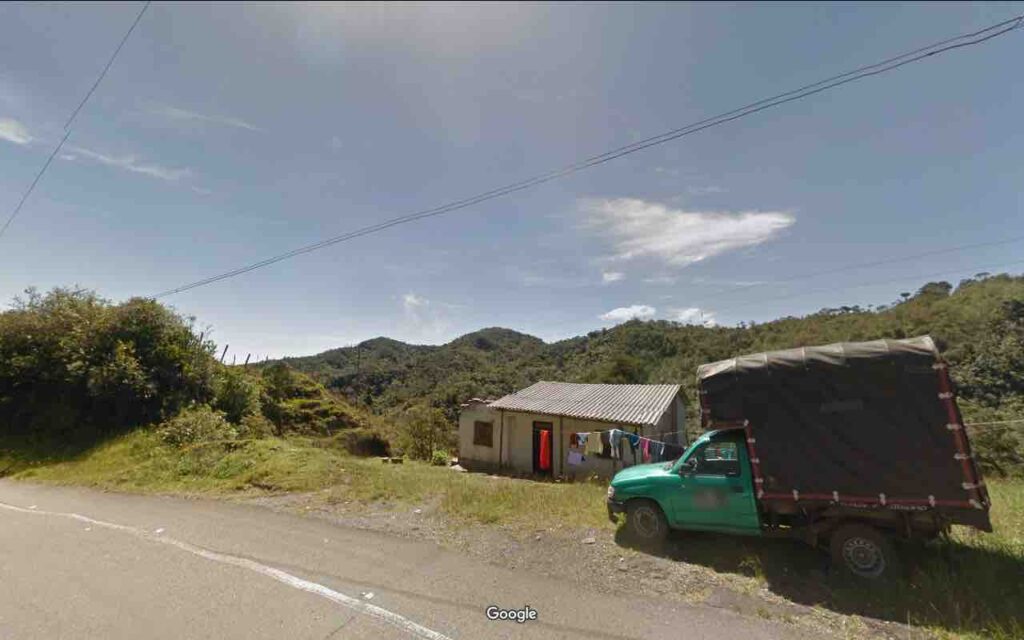

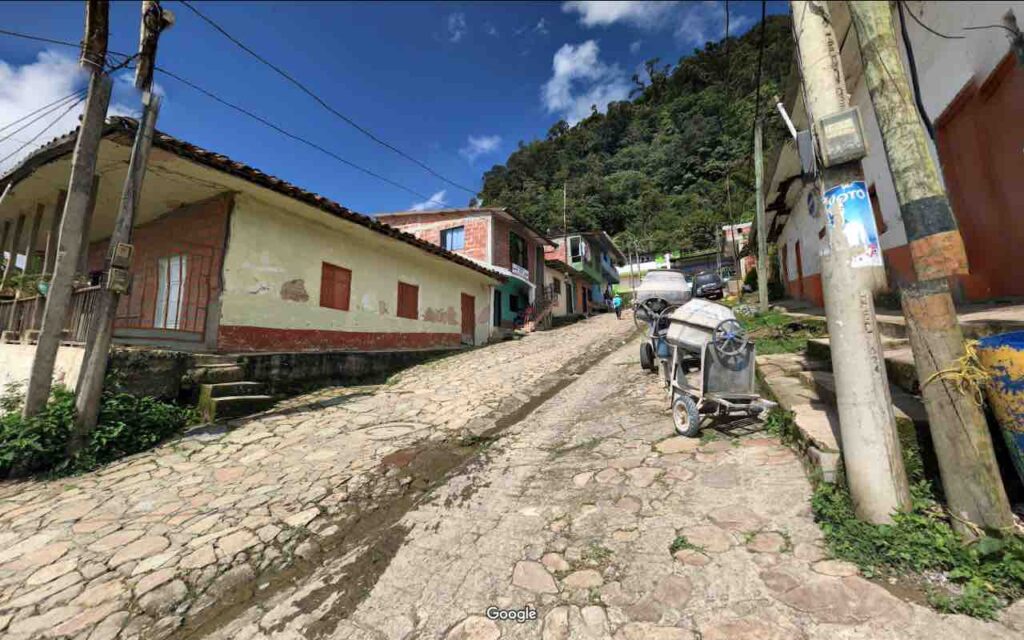

However, it will not take long before the traffic dies down, and you are once again climbing up and down, surrounded by the green, forested mountains and passing through the small towns.

Around every corner is another view. Atop every climb, seemingly endless green peaks extend as far as the eye can see.

After another 70 kilometers of brutal mountain running, toying around with 9,000 and 10,000 feet, you will drop down into the Cauca river Valley, between the Occidental and Central Andes. This is a long and narrow valley.

The terrain is flat, but you are now running at 3,000+ feet! You will pass through fields of sugarcane, cacao, bananas, corn, and rice watered by irrigation canals as well as large cattle ranches. In the surrounding mountains two thirds of Colombia’s coffee is grown. It is 230 kilometers of running thru this gorgeous farm country, periodically passing thru small villages, before you will come to the outskirts of another of Colombia’s notorious cities; Cali.

710 kilometers of Colombian are in the books. Cali is not as large as you might think, to be so internationally famous. Very much a Colombian city, there are numerous cycles (motorized and pedal) and tightly packed neighborhoods. It doesn’t seem so threatening, unless perhaps you translate the graffiti, such as; “menos agua mas sangre.”

After Cali you are heading into progressively less secure country, although the scenery of small farms is still around, it is more and more broken by forest.

By 800 kilometers you are reminded that you are in Colombia, as the road begins to climb into the mountains once again.

On the way to Popayan you start going on and off the main road, climbing on rough dirt roads. These grinding climbs, thru semi-frightening back country, cut off long kilometers on the looping highway, and afford you the opportunity to see places that no other tourist will ever visit. Behind you, the valley you left behind stretches out into the distance. From Popayan it is a grueling climb on a tortuous winding road to a mile high “plateau” at 910 kilometers. It is not exactly a plateau, as it is all hills, but the route mostly follows the ridgelines, so there are no more gutwrenching climbs… at least for the moment. Small houses still dot the roadside, huddled close to the pavement as it for safety from the forested hills that surround them.

After passing thru the tiny hamlet of Rosas you begin the long descent to the Rio Turbio. After you reach the Turbio at 1,110 kilometers you turn upstream and resume climbing on one of the most remote routes you have yet encountered. As you move up into the real high country, the forested slopes are gradually replaced by a stark and imposing view of jagged peaks and deep valleys.

After 1150 kilometers the climb gets serious. You come to Pasto, the last city of any consequence, at 8300 feet.

The climb continues all the way to the high point of our time in Colombia, at

10,500 feet at the Ecuadoran border in Ipiales. Beside you is the highest point in Colombia, the Cumbal Volcano, soaring overhead at 15,630 feet.

How to get across the Colombia-Ecuador border at Ipiales.

Ipiales is an easy border crossing. Go to the Colombian Immigration office. There will be a line outside on the right, but that is for Colombians. Go to the door on the left, show your Passport to the officer in front of the door and he will let you enter and tell you in which line to wait. Get your stamp with the date of departure. There is no Exit Tax for Colombia, do not pay if asked.

It is a 5 minute walk across the Rumichacha Bridge to the Ecuadorean Immigration Office. There will be a line in a cagelike corridor outside the building, but you will not need to stand in it. Just walk past and go straight inside. You will not be required to fill out forms, or present a proof that you are leaving. They will just stamp your Passport and you are free to go.

We are counting on those of you who reside or have visited these places

to enrich our file of pictures, information, and stories about the places we are visiting. Anything is fair game: Geology, History, unique places to visit, quirky local customs, you name it. We call this part “Boots on the Ground“. Nobody really knows a place better than someone who has their boots on the ground.

If we all share what we know, we can all have quite a journey around this planet. Don’t be shy. If there is one thing I have learned, it is that everyone I meet knows something that I don’t know. Your perspective will make everyone’s trip more enjoyable.

Please share your stories in the comment section below.

Colombia is much safer now than it was even 5 years ago. I have visited Colombia three different trips and have spent about a month each time. In 2010 many parts were still off limits because of the FARC. By 2014 many of the area had opened back up but when we attempted to go down one road a local woman said it was not safe, there had been sightings of marauding guerrillas. When I returned in 2019 the same woman had opened a little restaurant and a few rooms to lodge. She was doing well catering to the bird watchers of the world because that road has a few species found no where else in the world.

From a bird watching perspective, Colombia is THE place to go. It has over 1800 species (about 18% of the World’s species) of bird’s because it has such diverse ecosystems, ranging from Amazonian lowland rainforest to desert, to “sky islands”, to inter-Andean valleys to alpine and mountain habitat. They are still discovering new species of birds there, one of which is pictured below, a Hooded Antpitta. I was one of the first 10 people in the world to be shown the bird in the wild.

For all the multi sport teams here, you want some competition biking? Go to Colombia! On weekends and holidays you will see huge groups (100+) bikers climbing the roads up through the Andes. I saw a group out of Medellin beginning their climb in the morning. Their goal, 100k with an average grade of over 6%. They said many would not make it but would give it a good try.

One of my favorite running stories comes from Jardin, Colombia. Well, I should say, one of my favorite dog stories. I was staying in Jardin as part of a bird watching trip but I would go for runs either very early in the morning or during the mid day when the birds are quiet. Early one morning, around first light, I left my room and began running down a street toward the town square. In many parts of the world the family dog sleeps outside, often in front of the house. As I ran by one dog he got up and started to run with me. I tried to get him to go back but he stayed with me. As we ran by a second dog he got up and joined us and a third and forth dog did the same. As we entered the town square there was a very old dog laying in front of a store. He lifted his head and watched us run around the square. On the second pass he lifted himself up a bit higher and on the third pass he was sitting up. As we approached him on the fourth time around the square he slowly stood up and stepped off the curb and he joined us. He made the full loop around the square, returned to his spot and laid down. The remaining dogs and I made one more loop of the square and as we went past him he was sound asleep. As I ran back toward my lodging, as we passed the houses where the dogs belonged they would drop off returning to their spot in front of their house, until I was again running alone. Because the Latin culture tends to stay up late in the evenings they tend to start their day later as well. I don’t think a single family knew their dog had gone for a stroll around the town.

Thank you Joe for the lovely story! I wish someone took a picture of you and the dogs running around. It had to be just a jaw dropping seeing those dogs having so much fun with you.

Kids riding the “school bus”

Rhinoceros Beetle

Jardin Colombia

Girls, who when asked their age said they were 100 years old.

Old Willys Jeeps are used on coffee plantations but keeping them in excellent shape is a point of pride.

A young child paddling a dugout canoe. The stream’s color comes from the amount of tannin in the water

A view across the Colombian Andes

Haleconia, a plant loved by the various species of hummingbirds. Colombia has over 100 different species of hummingbirds

Huge cave that has nesting swifts and oilbirds. Oilbirds have so much oil in them that the ancients would take the dead ones and light them on fire, using them as torches.

One of the 1000’s of species of butterflies