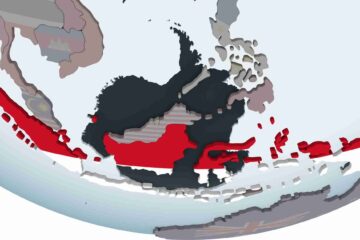

Region#6 Country#15: Timor-Leste

There could be no better place to begin our trip through the islands that surround the South and East of the Eurasian Continent than East Timor. The very existence of this tiny nation epitomizes the Region in which it lies…. Living at the crossroads of everything, absorb and adapt. The land absorbs and adapts. And the people that live on this land do the same.

You cannot really even begin to understand the presence of all these islands by looking at only the arc of volcanic islands across which we will travel. Those are in many ways similar to Central America, as the leading edge of the Indo-Australian Plate dives underneath the Sunda Plate on which Southeast Asia and most of Indonesia is located, pushing up the land like a bulldozer, and creating by its friction great pools of magma that feed the most active volcanic zone on earth… our route around the southern arc of Indonesian Islands.

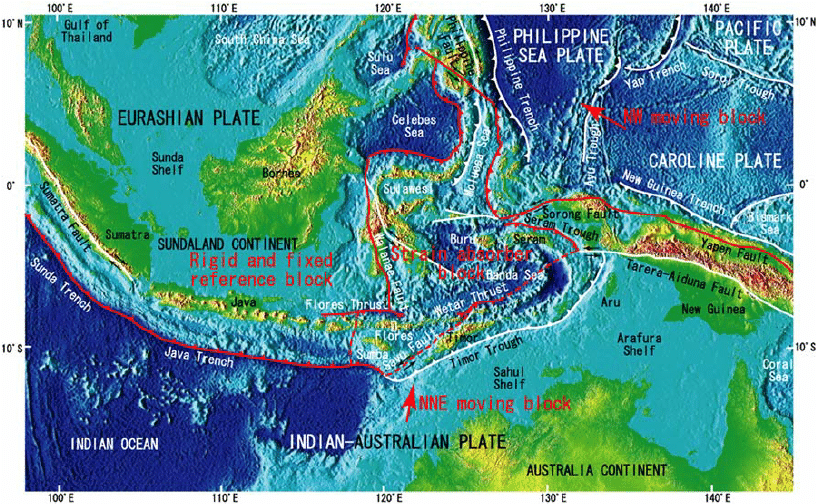

The thing is, Australia is not the only major plate pushing in on the Sunda Plate. From the North and East, the Pacific Plate is pushing in, and from the North and West it is the Eurasian Plate (of which the Sunda Plate is technically a part.) Caught in the middle of the collision of these three great Plates, the Plate on which Indonesia uneasily sits is being crushed from all sides. The result of this intense pressure are: the greatest concentration of fault lines where the very foundation of the land is breaking, Micro-Plates, as the edges of the colliding mega plates are broken off by the intense angular forces of the three plates colliding, deep ocean trenches, where one plate is diving under another, and volcanic zones ahead of the subduction zones.

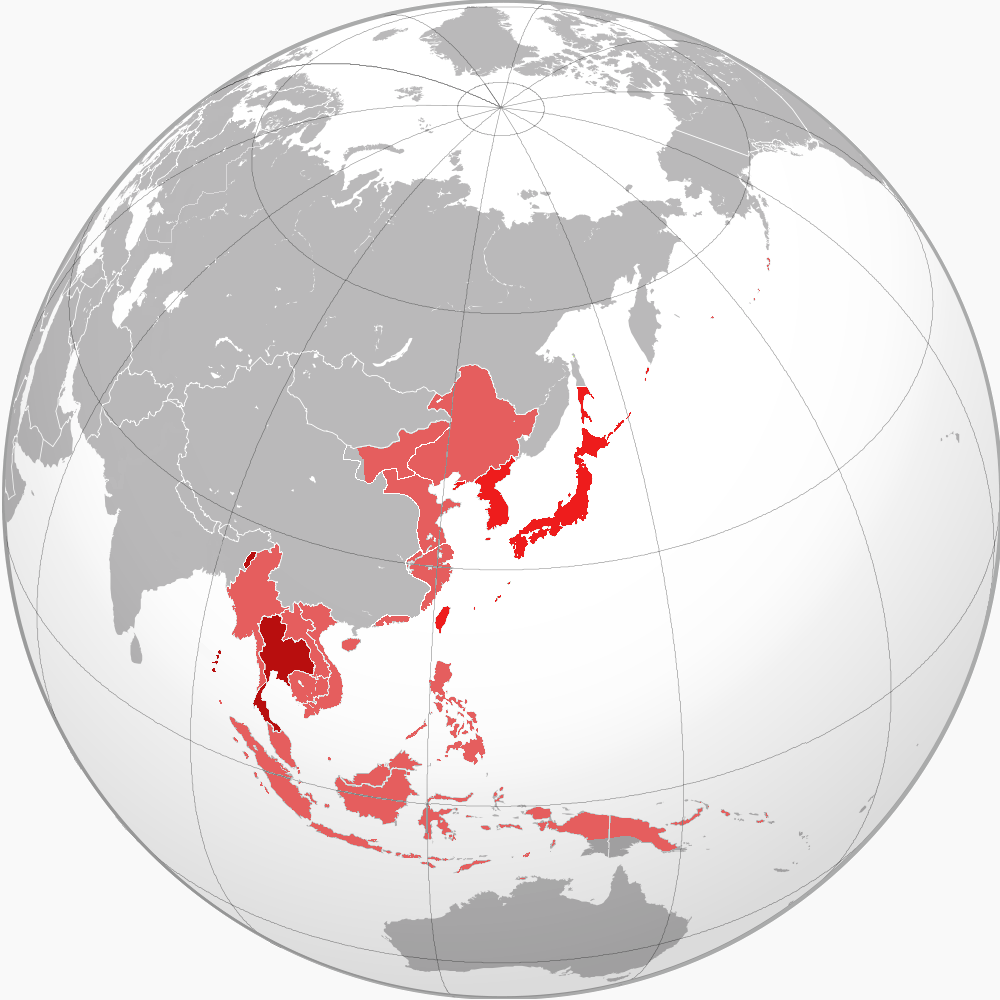

Now, draw back and look at a map of the entire area and you will see the outlines of the collision zones in the makeup of the islands. On the southern edge is the arc of islands you are going to run. They bow south in the middle as the Australian Plate sort of wraps around. On the north side is an arc of volcanic islands that match the leading edge of the Pacific Plate: New Guinea, the Phillipines , Taiwan, and Japan. In the center, pushed up by the force of the projecting finger of the Eurasian Plate being squeezed between the Pacific and Australian Plates is Southeast Asia and Borneo, the central island of Indonesia.

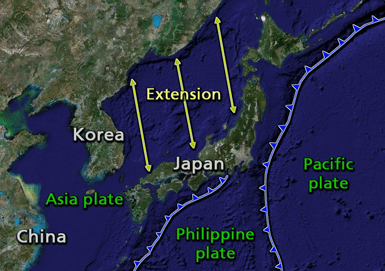

While all of these islands and archipelagoes are still in the process of formation, the dates of their origins highlight their separate identities. The oldest of them is the central Indonesian island of Borneo, which traces its roots back about 140 million years. Although the islands themselves are among the youngest in the group, the oldest volcano in our island arc goes back 85 million years. The Phillipines began forming about 65 million years ago, and the largest of the islands, New Guinea, is only about 30 million years old. Japan has a completely different origin, having originally been a part of the coast of Asia, and then pulled away from the continent by the forces of the Pacific Plate subduction under the edge of the Eurasian Plate over the last 23 million years.

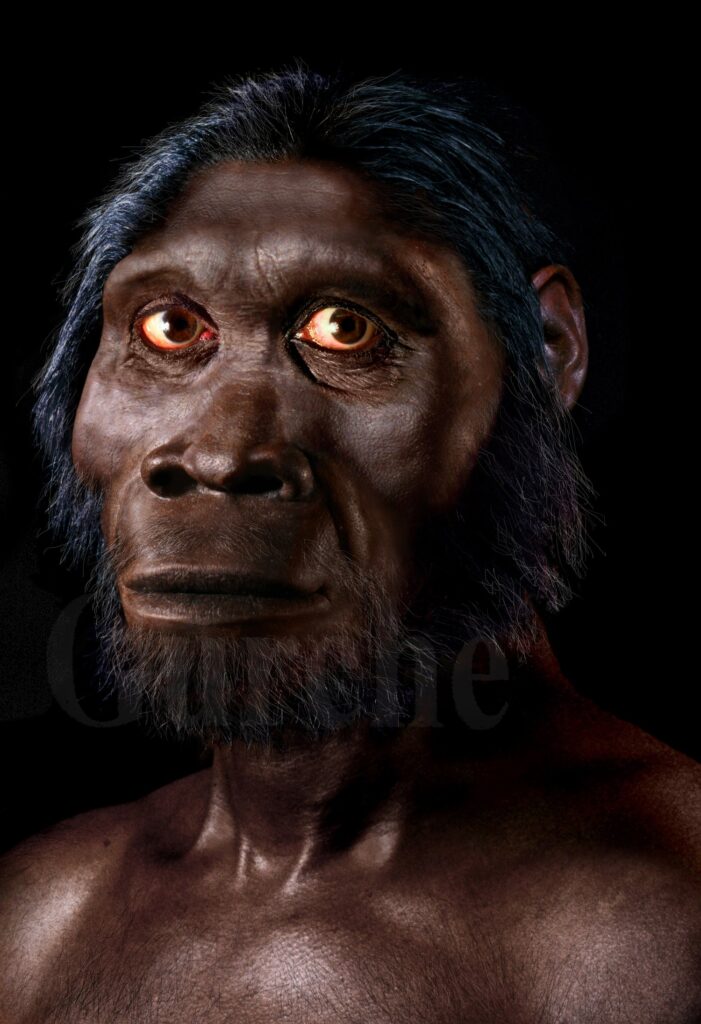

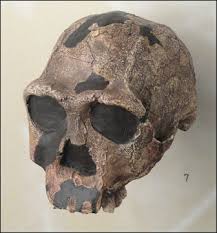

If you think the formation of the islands is confusing, just wait until we talk about how they got peopled. You have probably gotten used to every history beginning with; “Then we took it away from the indigenous people.” To be honest, it is sort of difficult to decide just who the indigenous Indonesia people are. We know this much. The first members of our genus to reach the Islands were members of the species Homo Erectus. Or do we know that? Oh, we know that Homo Erectus was there. We have the fossils… lots of them.

But, was he the first? Things got a little more complicated when we found the fossils of Homo Floresiensis. Floresiensis was a little bitty hominid, barely standing over a meter tall as an adult. And he had a remarkably small brain case. There was a sense that the first one found had to be some sort of genetic abnormality. Then we found more.

If there is anything we humans have always done, it is fit anything new into our pre-existing belief system. The only tiny, humanlike ancestors, with braincases that small, are species we know never left Africa. Therefore this population had to be a dwarf variety of Homo Erectus. Floresiensis presented us with one more problem. We have long known and accepted that Erectus had somehow mysteriously died out long before the arrival of Homo Sapiens on the Islands. That accepted fact got a little more shaky when the latest bone bed turned out to be barely over 100,000 years old. The gap between the accepted departure date of one, and the arrival of the next was getting ever smaller. Floresiensis, our miniature Erectus, was still around until about 50,000 years ago. Just about the time that Homo Sapiens arrived. Coincidence?

The US calls itself “the melting pot” because of the waves of immigrants who came here and intermingled. But the real “melting pot” has to be the Indonesian archipelagos. That first wave of immigrants that came from Africa, and followed the Equatorial band across the planet arrived in Sundaland (Indonesia during low sea levels when it was a single land mass connected to present day Southeast Asia) went on to populate Australia.

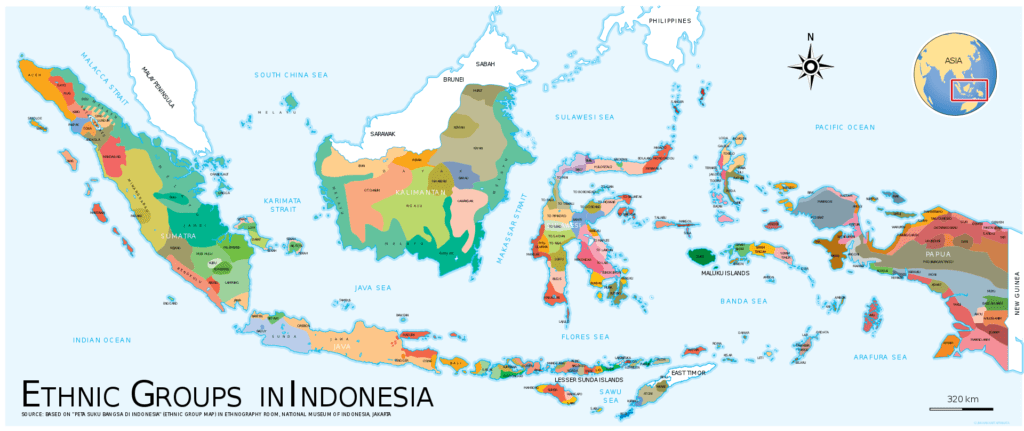

After modern man had spread to the corners of the earth and adapted to their local conditions, wave after wave came to Sundaland. The first wave came from present day Viet Nam. Others soon followed; Austronesians from Taiwan (who constitute the majority of present day Indonesians), Indians from India, Arabs from the Arab Peninsula, Chinese from China. What developed was a mélange of different ethinc groups; admixtures of different races as well as relatively homogenous populations that had remained in situ from the time of their arrival. The result of this diversity is a single country with over 700 languages, in a number of different lingual groups.

To make administration possible, there is an official Language called Indonesian (reminiscent of Hindi in India) which is a standardized form of Malay with a heavy dose of words from Regional Languages, as well as Dutch (more on the Dutch later), Sanskrit, Portuguese, Arabic, and English. As a language it is primarily used for commerce and education, and Indonesians speak it with varying degrees of proficiency, while carrying on normal discourse in their native/regional language. Being multilingual is pretty much a necessity. If you can speak Portuguese it will hold you in good stead during your trip across East Timor, while Dutch will be more useful during the remainder of your trek across the islands.

For tens of thousands of years the people of the islands practiced their tribal animist religions. By 200 BCE Indian influence was spread across Southeast Asia and the Islands, and a number of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms rose and fell. Somewhere near the end of the 1200’s Islam arrived in northern Sumatra. At first it spread slowly, but it spread inexorably. By the 1600’s Islam was the majority religion throughout the islands. Religions, like the waves of immigrants, and the great natural forces bearing down on this seeming focal point of the earth were absorbed, and adapted to Indonesia.

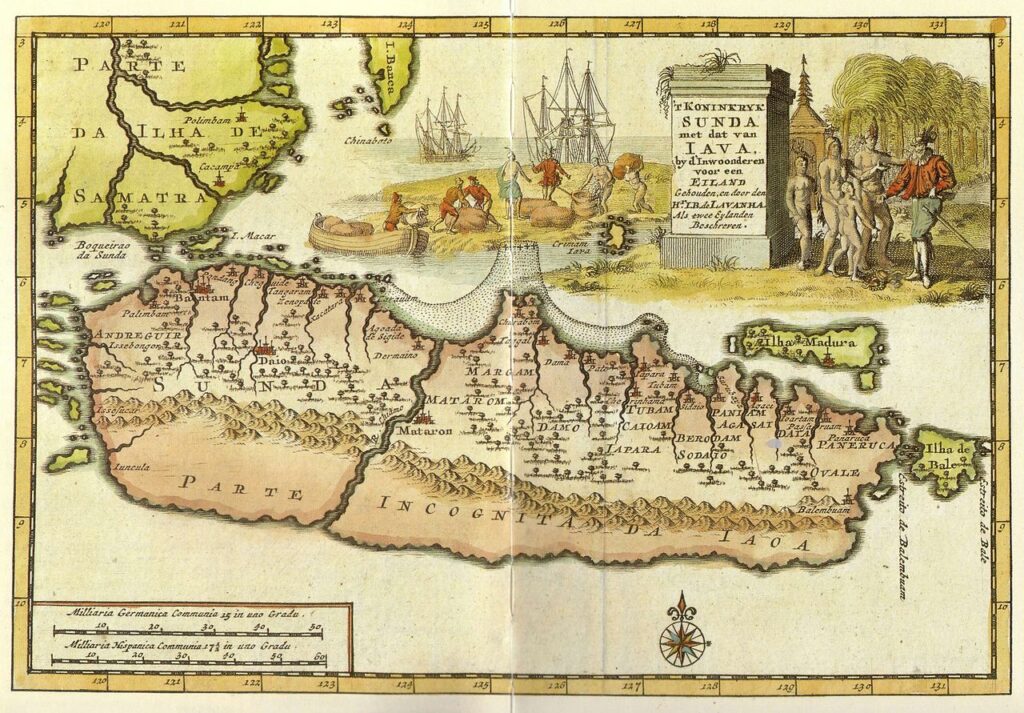

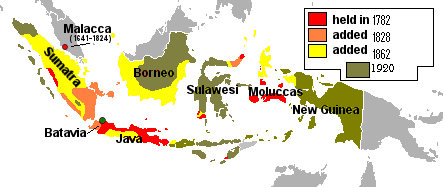

In the early 1500’s a new power arrived on the scene. It was the Portuguese. The Islands were the source of turmeric, cumin, cinnamon, coriander, lemongrass, lime leaves, ginger, galangal and nutmeg. The Portuguese came to seize control of the trade in spices. Conquering and colonizing the islands was a more challenging task than it was in the New World, or in Australia. Jungles give better cover than deserts, and the local population was not ravaged by diseases that were nothing new. While they did not escape without some defeats, the Portuguese established trading posts, forts, and missions on a number of Islands. Based in the conquered city of Malacca on the Malay Peninsula, Portugal at least disrupted the trade routes of other European powers.

90 years after the Portuguese first moved into the islands, the Netherlands created the Dutch East indies Trading Company. Despite having not a square inch of territory in the islands, the arrogant Dutch awarded the Company exclusive rights to the spice trade.

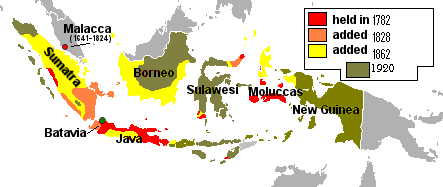

Nothing great is achieved without great goals, and the Dutch proved to be astute conquerors. They had superior ships and arms to those of the Portuguese, and were better financed. But it was tactical and strategic superiority that made the difference. Having established a foothold on Java, the Dutch exploited the internal politics and rivalries of the multitude of local kingdoms. Gradually they took control of Java, and then expanded out to the other islands, gradually expelling the Portuguese in the process. The Dutch East Indies Trading Company became the single most valuable business on earth.

There was an interlude in 1800. The Napoleonic Wars were raging in Europe and the Company was dissolved and the assets confiscated by the government. Then, to make things worse, Napoleon conquered the Netherlands and installed a puppet government. The British East Indies Trading Company took advantage of the situation to seize Java. Unlike this same time period in Central and South America, the situation did not lead to an independence movement among the colonists. Perhaps they were just too few in number, or had insufficient force of arms and did not have the ability to hold the islands without the military support of the mother country. Whatever the reason, after the Napoleonic Wars ended, the British gave back Java and the Dutch State took over the business.

This was when the ugly business of subjugating and colonizing began in earnest, and with it the serious atrocities that the islands had largely been lacking. The Dutch rule over the islands was tenuous at best, and frequently resulted in armed conflict. However, they maintained control by sometimes extreme force. The outcome of this was not all bad. The road networks, railways, bridges, and irrigation systems built by the Dutch forced labor became the structure on which an independent Indonesia would one day be built.

In the early 1900’s an independence movement took root among the Indonesian people. It was suppressed vigorously by the Dutch. Then came WWII. Germany conquered the Netherlands early on, leaving the Dutch colony somewhat isolated, and the exports of materials from the Islands previously scheduled to go to Japan were diverted to the US and Britain. Meanwhile, the Indonesian independence movement contacted Japan to ask their assistance in overthrowing Dutch rule. By March of 1942 Dutch forces had been expelled from the islands.

Sukarno, who would become the first President of Indonesia rallied the Indonesian people to support the Japanese war effort, and it became a major supplier of war materials. Our picture of Japan during WWII was as an aggressive power, seeking to build an empire. And such a view is not without merit. But we seldom if ever hear the stated objectives from the Japanese side. The Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere was a sort of Asia for the Asians campaign. Japan was to throw out the European colonial powers and establish independent states across Asia, with Japan as the leader. At best, Japan was not a benevolent occupier. It is estimated that 4 million Indonesians died during the Japanese occupation. None the less, by 1945 Sukarno and the Japanese put together a constitution for Indonesia and set August 24 as the date to announce Indonesian independence. The plan was to include Portuguese Timor (where you are right now) and British Borneo and Malaya in the new country. Of course, Japan’s surrender made that announcement impossible. So Sukarno unilaterally announced independence on August 17.

The Dutch were not so anxious to give up their prize, and set about retaking the islands. Despite being badly outgunned (Many Indonesian soldiers went into battle armed with bamboo spears) the Indonesians put up a fierce resistance. With the help of the British, the Dutch retook most of the islands over the next 4 years, but the fight was costly (more British and Dutch troops died trying to retake Indonesia than were killed defending it from the Japanese). Not only that, it was not particularly good PR to try and rebuild an empire at that point in time. On December 17, 1949 the Dutch finally recognized Indonesian Sovereignty.

Now, at last, after all this long exercise in laying the groundwork, we get to why Timor-Leste is the perfect place to start your trip through the islands. You see, the place we now call East Timor never stopped being a Portuguese colony. It was neglected. It was ignored. But it was still administratively separate from the other end of Timor. And if there is one thing we have seen in country after country during our trip around the world, former colonies cling doggedly to the artificial boundaries set up by their European conquerors. When Indonesia finally was freed from Dutch rule, they ended up with the exact same borders as the original Dutch colony. the British Possessions remained British, and East Timor remained a neglected Portuguese colony.

In 1975, Timor-Leste finally achieved independence from Portugal, and was promptly annexed by Indonesia. It fought for independence until UN peacekeepers were sent in 1999, and finally, in 2002 Indonesia granted it its independence. From this distance it is difficult to understand why the willingness to die for a boundary arbitrarily set up by Dutch and Portuguese invaders. I guess after these colonial boundaries have been around a few hundred years, people come to embrace them.

Now for your journey; Upon your arrival in Timor Leste the first thing you are going to notice is that you are tall. Really TALL! Timor Leste has the distinction of having the shortest population on earth. The average Timorese man is 5’ 2.9” tall (less than 160 cm). The average Timorese woman is 4’ 11.5” (just over 151 cm). Not that the rest of the Indonesians are towering giants. Men average 5’ 4.39” and women 5’ 0.15”.

The first town you will reach when you leave the beach is Betano.

You can start your day like a true East Timorean, with a hearty bowl of Batar Daan; corn, mung beans, and pumpkin. This is pretty much the first hint as to why the Timor Leste are the smallest people on earth.

But, since the primary occupation in Timor Leste is subsistence farming, your choice will be mostly vegetable fare. Mostly they grow rice; lots of rice. Also grown are sweet potatoes, maize, cassava, and taro. These primary staples are supplemented with beans, cabbage, spinach, onions and cowpeas.

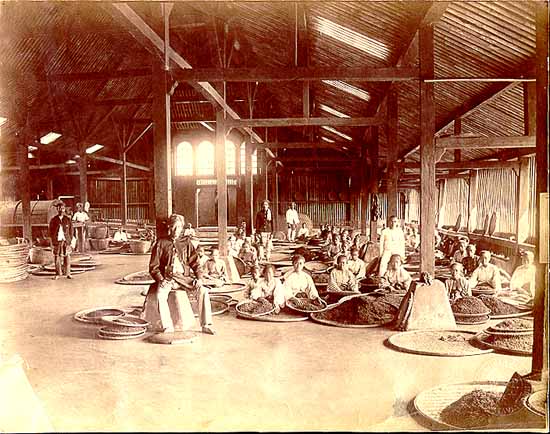

About the only employment is as a laborer on the coffee plantations, where they will make only a few hundred dollars a year.

After climbing the small rise to Betano, you will drop back down to a coastal plain and follow narrow dirt roads for the remainder of your 110 kilometer trip to the Indonesian Border.

You will pass by farms and small villages, and you will see lots of motorcycles. Sometimes you will just be in the countryside. If you get a chance, you can try one of the meals that you will only find in East Timor during the trip; Feijoada. It has pork and chorizo, along with cannelini or sometimes black beans. This is a Portuguese dish that you might find in other Portuguese colonies.

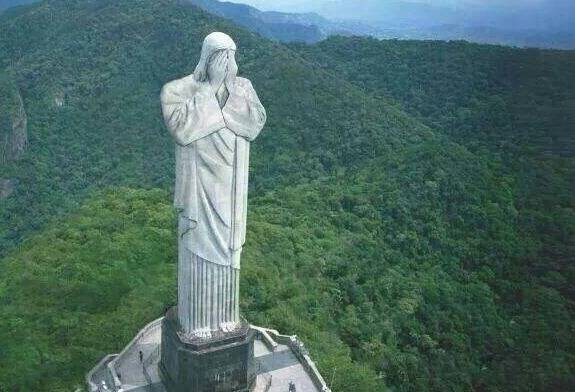

While you are in Timor Leste, you might want to take a side trip to the capital of Dilli. The main attraction there is the giant statue of Christ. It is hard to look at it without wondering if it is meant to be a statement about the state of the city it looks down on.

Another experience that you really ought to try is sampling the staple food called akar. It is a dry sort of pancake made from the pounded bark of palm trees. By all accounts it looks and sounds better than it tastes.

But it is a staple food in a country where there are only two seasons; the wet season and the hungry season. Little wonder that 60% of children under the age of 5 suffer from chronic malnutrition.

At last you will come to the border crossing at Motamasin.

Crossing from Timor Leste to Indonesia:

Tourists do not generally enter Indonesia by land. Most arrive at airports and many will arrive at ports. Fortunately, unless you are among the lead teams, they will have seen a lot of CRAW already. Still, do not be surprised if you are selected for a special interview. They will take you to a room where your bags will be searched and you will be asked many questions before they send you on to customs.

At customs they will search your bags again and ask the same questions before sending you on your way. Only occasionally will they decide to detain you for a few days.

Two things to consider, though: any sort of drugs will have you praying to get off with 4-20 years in prison, as opposed to a potential death sentence. And being a foreigner does not help you any. Indonesia likes to make an example of foreigners. And, lastly, this is not Latin America. Do not even think about trying to bribe the border officials.

Welcome to Indonesia!

We are counting on those of you who reside or have visited these places

to enrich our file of pictures, information, and stories about the places we are visiting. Anything is fair game: Geology, History, unique places to visit, quirky local customs, you name it. We call this part “Boots on the Ground“. Nobody really knows a place better than someone who has their boots on the ground.

If we all share what we know, we can all have quite a journey around this planet. Don’t be shy. If there is one thing I have learned, it is that everyone I meet knows something that I don’t know. Your perspective will make everyone’s trip more enjoyable.

Please share your stories in the comment section below.

Team Dana has finally made it to Region 6. This is particularly interesting for me as I spent 2 months travelling from East Timor (then a province of Indonesia) to Jakarta in 1990 along much the same route we are traveling.

I actually flew into Kupang from Darwin. I had been on a year long trip from Africa to Australia and New Zealand. I had found work in several places but at this point there was a recession in Australia and nary a job to be found. With funds dwindling, I realized I could remain in Australia for a few weeks or south east Asia for a few months. After a few days in Kupang I headed up to Dili.

At this point life was fairly peaceful in East Timor. A few years earlier fighting had been intense. There were a few abandoned and bombed out tanks and amphibious landing craft in the harbor but the people were extremely friendly and inviting. I stayed at a losman (think youth hostel) to the east of downtown near the water. A few other guests and I rented a car and drove into the hills. The countryside was beautiful. After a few days I continued down the coast to Baucau. That town was a little more bombed out and down on its luck. The market was beautiful but I remained only a short while before returning to Dili.

About a year later war broke out again. Sitting back at the University of Wisconsin, it broke my heart. Such warm memories of the place.