Region#4 Country#13: Antarctica

And then we come to Antarctica. Dark, brooding, mysterious Antarctica….

How, you have to be wondering, can I call a continent of glaring white dark and brooding? Because Antarctica holds her secrets close. A mile and a half of Ice covers her land, extreme temperatures have made her the only place on earth that man has never been able to conquer. She holds tightly her dead and their secrets. On the last outpost before reaching the Continent, the Sandwich Islands, a skull and femur were found. They belong to an indigenous woman from the tip of South America. How she came to be there, no one knows. Others have been swallowed up by her; explorers who vanish into the wasteland, never to be seen again; scientists eaten, along with their vehicles by yawning crevasses hidden by snow. Her actions have been unknown; unseen and unheard. Her origins buried in the ice. Antarctica has held her secrets close. And only in the last few years have we begun to catch a glimpse of them.

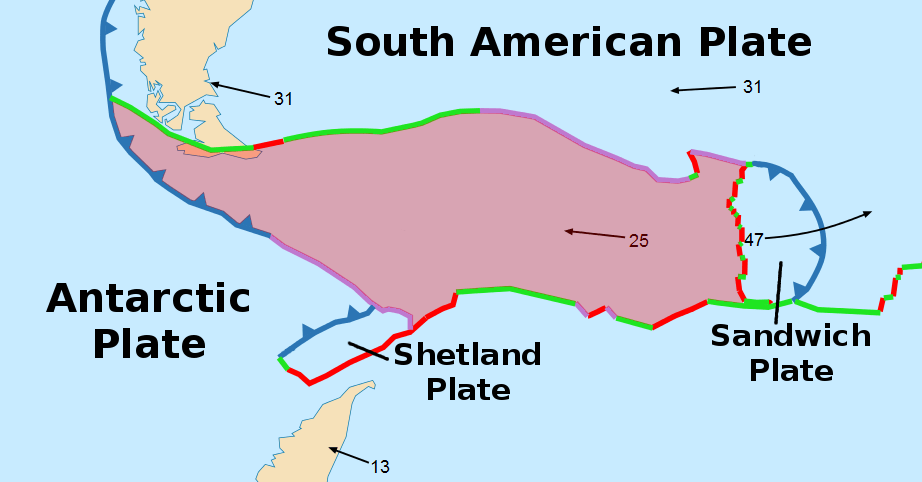

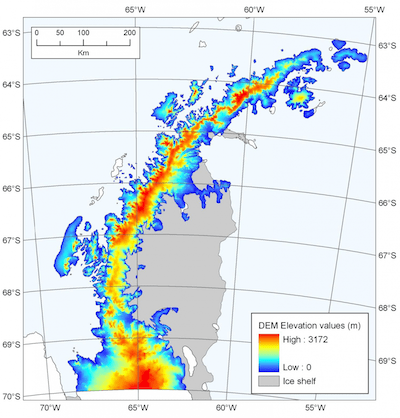

You might think that the geology of Antarctica would be a little more boring than the minefields of tectonic activity that we have been traveling thru. Think again! During your flight from Ushuaia you crossed from the South American to the Antarctic Plates. Had we held this event 50 million years ago, there would have been no need for the Dornier, because Antarctica was connected to the southern tip of South America, and the Antarctic Peninsula on which you will land was an extension of the Andes. 50 million years ago the Antarctic Plate and the South American Plate began to split apart, with the Drake Passage forming between them. This is quite different than the tectonic collisions we have been traveling across. The Plates have been spreading and not colliding, with the gap growing so wide between the two that a small new plate has formed between them, the Scotia Plate.

The turmoil around the edges of this plate has resulted in the formation of islands around its boundary which have, over the past 50 million years, alternately risen above the surface of the sea, and been submerged beneath it. Currently there are four islands or groups of Islands marking the boundary of the Scotia Plate… the Falkland, Sandwich, and Shetland Islands, along with South Georgia Island.

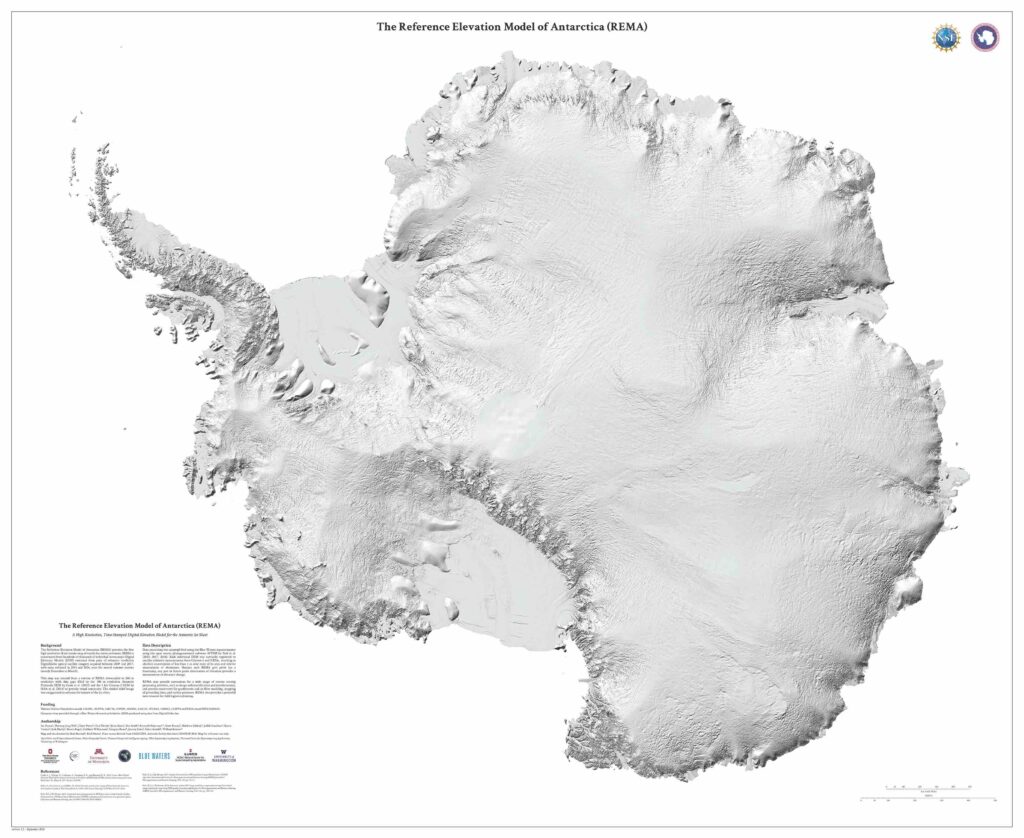

The substance of the Antarctic Continent has been, until the 21st Century, a greater mystery than the makeup of other planets. It is, perhaps, the least known landmass in the solar system. The mile and a half of ice that covers most of the continent is a more effective shield than millions of miles of space. And the incredibly hostile weather conditions place extreme limits on exploration.

However, this century has seen a great increase in knowledge about what lies under that ice. If you remember what was taught in school when we were kids, you might think that we will finally be out of the reach of earthquakes…. But the placement of more sensors has revealed that Antarctica actually has as many earthquakes as the other continents. It just previously had fewer sensors. And not only are you going to have the treat of feeling earthquakes rock the ice, Antarctica has a whole different form of shaking, icequakes; especially during the summer. It seems the summer sun

“warms” the upper layers of ice, even creating some melt during the day. When the shrinking of the surface layers in the “heat” is followed by the expansion of refreezing at night, the layers of the entire surface have to adjust. Antarctica is not some unchanging land, frozen in place by a thick sheet of ice. It is a living, breathing entity, cloaked in ice and daring any to uncover her secrets.

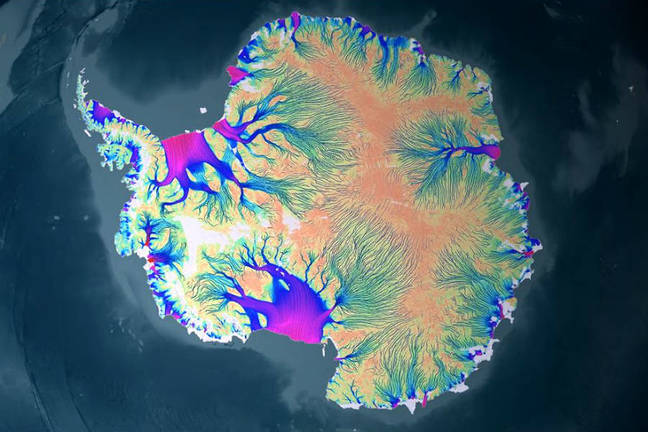

And she is not just a graveyard for those who have tried to invade her space. A sleek European Satellite called GOCE (if you want to know, although you will soon forget, that stands for Gravity Field and Steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer) measured the gravitational fields of Antarctica from low (155 mile) elevation until 2013, when it re-entered the atmosphere and joined all of the other dead hidden in the ice.

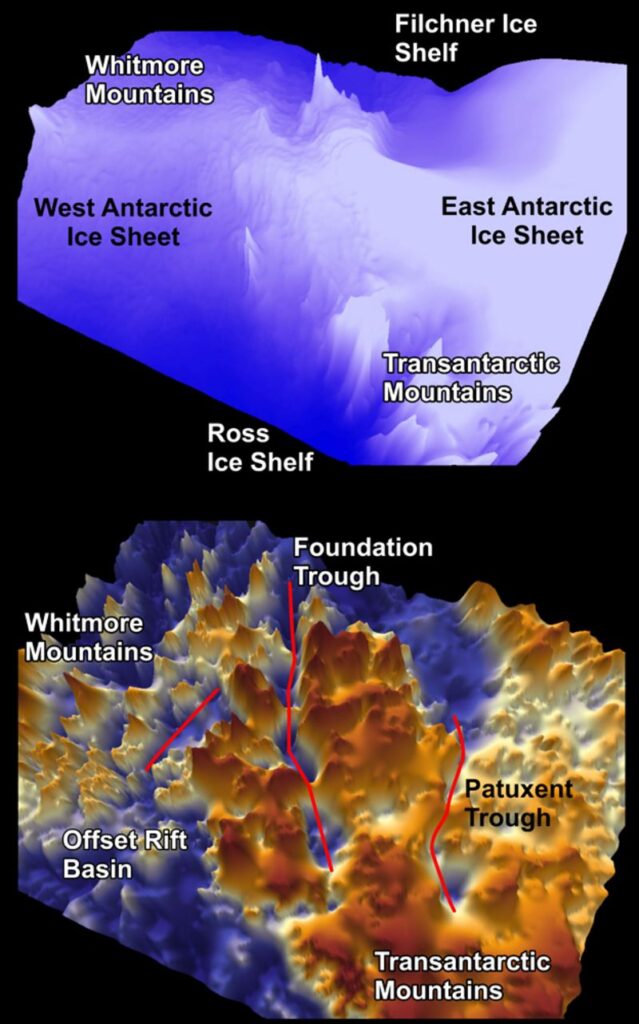

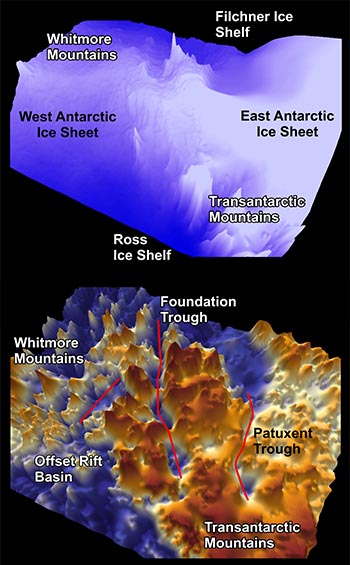

By 2018 scientists had pieced together from all that data a picture of what lay under all that ice. And what they found was a graveyard of dead continents, as the Antarctic bedrock was not the expected homogenous mass locked under the ice, but instead was the cobbled together remnants of three continental cratons. A craton is the stable crystalline rocky core of a continent, to differentiate it from the masses of material that are bulldozed up along the edges, or that accrete on and erode from its surface. The origins of these dead continents remain a mystery, as well as when they were jammed together.

If East Antarctica has its secrets beneath the ice, West Antarctica is not to be left behind. You might have heard of Mt Erebus. Sitting on Ross Island in McMurdo Sound, Mt Erebus is the southernmost active volcano on earth. We will pass near it towards the end of our trek across the continent of ice. What was discovered in 2017 was the largest volcanic region on earth, stretching from McMurdo Sound to the base of the Antarctic Peninsula there are 91 volcanoes hidden beneath the ice. Add those to the 47 known volcanoes in Antarctica, and the continent has an impressive 138 volcanoes, about which we know almost nothing, except that they exist. Truly, this is a continent of mysteries.

West Antarctica is also home to some amazing valleys. Not discovered until 2019, there are three deep valleys cutting through the Transantarctic Mountains from East Antarctica to West Antarctica near the South Pole. The Foundation Trough is 350 kilometers long and 35 kilometers wide. The Patuxent Trough is 300 Kilometers long and 15 Kilometers wide. And the Offset Rift Basin is 150 kilometers long and 30 kilometers wide. These are not the only canyons hidden under the ice in Antarctica, but they are the ones that the ice saves you from crossing. In East Antarctica the deepest canyon in the world is hidden under the ice. Under the Denman Glacier is a canyon that extends 11,500 feet below sea level. Were the Antarctic ice to melt, it would become the world’s deepest fjord by almost twice. Currently the deepest is the Skelton Inlet at 6,342 feet. Of course, if that happened all the fjords on earth would be 230 feet deeper.

Of course, the most outstanding attribute of Antarctica is not a secret. The weather is going to be right in your face. This is the coldest, and most inhospitable climate on earth.

You can’t start any conversation about the Antarctic weather without talking temperature. The highest temperature ever recorded in Antarctica was 69.3 f (20.75 c). If it provides any encouragement, that was last summer, and most of us will be traveling thru Antarctic during the balmy summer temperatures. You definitely don’t want to be there in the winter, when the lowest recorded temperature was -144.4 f (-98 c). I hate to tell you, but that was up in the ice domes, exactly on your route. At the actual South Pole, which we will swing around to make our turn for the north coast, the highest temperature ever recorded was 9.9 f. The coastal areas are warmer, and the Antarctic Peninsula, where you will start is the warmest part of Antarctica. We are not promising that it will happen during your trek across. But I understand it has actually rained there before.

Not that precipitation is expected to be an issue. Antarctica is already the world’s largest desert, averaging continent-wide only 6.5 inches of precipitation a year. Of course continent-wide is meaningless. The real question is how much precipitation to expect along our route. Our start, on the Peninsula, is about the warmest and wettest part of Antarctica. The first 2900 kilometers will be mostly spent on the east side of the Transantarctic Mountains, over half that distance spent coming down the peninsula. The rest of the east side of the mountains should be about average, but once we cross the Transantarctic Mountains to West Antarctica, we will be in the snow shadow, where the annual precipitation is less than 2 inches. Of course, the real enemy is not the amount of precipitation. It is the extremely low humidity due to the temperatures. I am not going to sugar coat this. Your lips will crack and split. Your skin will become so dried out that you look like a burn victim. That dry skin is going to chafe like no chafing you have ever experienced. Crossing Antarctica on foot will be no picnic. The funny thing about your experience on the world’s largest desert… 70% of the world’s fresh water will be under your feet. Very little precipitation falls, but it never leaves. It comes down frozen, and makes its way to the sea, but at a glacial pace… literally.

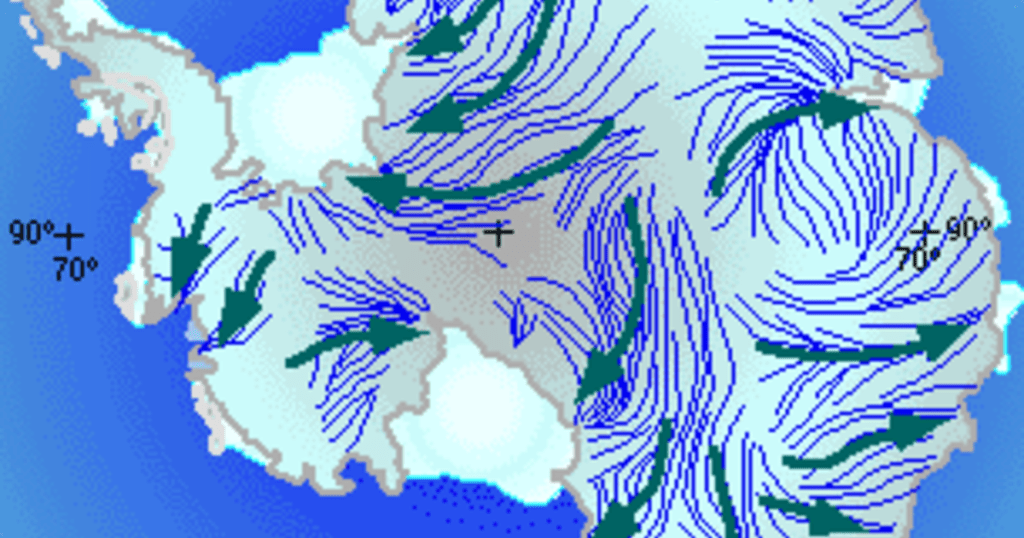

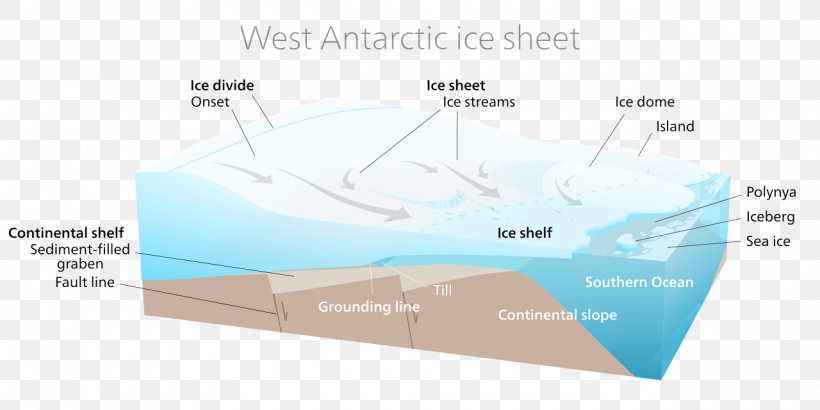

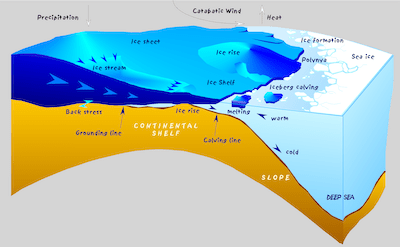

The last obstacle might be the one that breaks you. It is called the Katabatic Wind, and there is nothing else like it on earth. The supercooled air from the high elevations cascades down the ice fields to the ocean, picking up strength as it goes. Hurricane force winds will be the norm over much of your journey. You will experience strong winds during the duration of your journey, but you won’t hit the Katabatic Winds until you leave the Ronne-Filchner Ice Shelf at around 2,000 kilometers. From there to the South Pole you will face constant wind in your face. After you cross the Transantarctics it will be at your back all the way to the west coast. Again, for what comfort it might bring, the Katabatic Wind has never been known to top 200 miles an hour.

Now for the meat of the Travel Guide; a blow by blow description of where you will be going. I think this is a good point to make it clear that no one will blame you if you simply stay in the Dornier and return to Ushuaia. Antarctica is a tough trip, and we are expecting to lose quite a few of you along the way. As if the hidden crevasses large enough to swallow even the Sno Cats we have for your support vehicles, 100 below temperatures and 200 mile an hour winds are not enough, that is just the everyday stuff. You will also be in peril of whiteouts and blizzards of a previously unimagined intensity, which could last for days. And even the Sno Cats will not be able to follow on some of the mountain passages, where any misstep could leave you injured and beyond the reach of rescuers. No one would blame you if you turned back now.

A rubber raft will land you on an unnamed beach on the west side of Graham Land, between Anvers and Renaud Islands . The Sno Cat will only be able to accompany you for less than 20 kilometers, as you will climb rapidly up the spine of mountains running down the center of the Peninsula. By 30 kilometers you will be nearing the top at about 10,000 feet. You will traverse the ridge that extend out into the projection of land on which you landed for about 10 kilometers before turning to the right at the main ridgeline, crossing thru and descending to the east side of the Peninsula… I am thinking that, on this section of the course, snowshoes or even cross country skis will be preferable. In line skates and bicycles will be at a decided disadvantage. A Sno Cat will meet you again at about 70 kilometers.

Between meeting the Sno Cat and 150 kilometers you will make your way steadily down towards the bay that is filled with Larsen Ice Shelf C. This will be easier going than crossing the mountains, but the best track of all will come when you reach the Ice Shelf.

Now, you may have been hearing about chunks of Larsen Ice Shelf C the size of states breaking off and floating away. And that is true. However, our course is still many miles away from the open ocean. The Ice Shelf will provide 360 kilometers of smooth sailing with your Sno Cat right with you, rather than the arduous trek thru the high mountains carrying all your supplies. Besides, if a state sized hunk of the shelf should break off, it isn’t like it would melt right away, and it sure isn’t going to turn over. We should be able to whisk you off of it with relative ease and put you back on intact ice. There will not even be a time penalty. Just be careful if you happen to notice a rift appearing; altho it is unlikely that you would try to cross if you came to one.

Coming ashore west of Hearst Island in Palmer land, you will cross over the Transantarctic Mountains to the west side once again, this time through a relatively easy saddle in the range. On the west side you will pass by Mt Hope, the highest point in British Antarctica at 10,627 feet, and drop down onto the Dyer Plateau.

Once on the Dyer Plateau, you will once again have relatively smooth travel for a considerable distance. This time you can travel without the discomfiture of wondering if your course might break off and float out to sea.

A little past 800 kilometers you will be able to see mighty Mt Jackson (10,444 feet). Up until 2017 Mt Jackson was heralded as the highest peak on the Antarctic Peninsula, before a new survey revealed that Mt Jackson was 55 feet less and Mt Hope was 377 feet higher than previously believed. While not creating the kind of public outrage as demoting Pluto from being a planet, this has created quite a controversy among the native Antarcticans, who can be divided between the proponents of Mt Hope and those who feel Mt Jackson deserves a recount.

After passing Mt Jackson, you will climb over the more gradual slopes of the Sweeney Mountains before dropping down into Ellsworth Land where you will reach the Evans Ice Stream flowing into the Ronne Ice Shelf at 1,570 kilometers. You will then travel 320 kilometers across the Ice Stream to the Fowler Ice Rise at the base of the seven summits of the Vinson Massif.

The Vinson Massif has the highest point in Antarctica at 16,660 feet. All of the Peninsular mountains are popular with climbers, but naturally Vinson is the best most popular. You might even pass by some expeditions on their way to one of the summits…. But I think you will count yourself lucky that you are just looking at it from a distance. And even luckier to see another human being!

An ice rise is where the flowing ice crosses high spots in the sea floor. While it might appear to be nothing more than a bulge in the otherwise flat Ice Shelf, the stress of the bending ice in Ice Rises expedites the formation of crevasses. And the Foster Ice Rise is one of the largest. When you come to it, it will appear to extend from the base of Vinson, and extend out onto the Ice Shelf until it is out of sight. Treat it with respect.

Things will not get better when you come off the Fowler at about 2,000 kilometers. Having finally gotten off the Peninsula, you are finally going to meet the Katabatic Wind head on. Naturally, leaving the Ronne Ice Shelf, now you are in Ronne land.

At this point it is only 920 to the Pole, where you will turn towards the coast again. You start out on just a sloping ice field, climbing into the teeth of a constant wind, up towards the Patriot Hills, a spur of the Transantarctic Range that you will have to cross to reach the Pole.

The Transantarctic Mountains to your right are decreasing in height until you pass a place known as the Bottleneck. Millions of years of precipitation have collected on the ground, until the accumulated ice is higher than the lower mountains. In East Antarctica, where you are rollerblading your way towards the Pole, every year there is 4 times as much snow as in West Antarctica, in the snow shadow on the other side of the Transantarctics. Naturally, the accumulated ice is many times deeper, so it is flowing thru the Bottleneck, from East Antarctica into West Antarctica, and you are crossing that current. Fortunately, the current speed is not such that it will carry you away, but if you fall into a crevasse, over a Few thousands of years you would end up in West Antarctica.

Just before you reach the Patriot Hills, you will come to the Patriot Hills Base Camp (2650 feet elevation). There, the Blue Ice Runway offers one of the few evacuation points, if you decide that you have had enough fun on the ice. If not, we still have a special treat, as there will tents there to provide you comfortable accommodations as well as a chance to inspect the chafing that has been taking place inside your clothing!

After you leave the luxuries of Base Camp, then you must cross the patriot Hills to reach the Hercules Ice Dome.

Now, the Hercules Ice dome is not a feature that is going to create a big impression visually. It will just look like a sloping ice field from the ground.

The real treat on the Ice Dome is the night skies. Ice Domes have long been the preferred location for drilling ice cores for climate research. It is less known that they are probably the best location on earth to look at a night sky unfettered by atmospheric disturbance. As you cross the top of Hercules, at about 9500 feet, you will probably miss the best of the show if you are there in the summer. But if you arrive when there is a night, you are going to be treated to night skies that few have ever experienced.

Ice Domes are another unique feature. Essentially the ice is distorted as it flows over rises or depressions in the underlying ground. It is the same thing you can observe in a stream flowing over big rocks… except at a much slower speed. It is similar to an Ice Rise, except those occur in an ice sheet flowing over submerged land formations. You have been lucky so far, and the Hercules is the first Ice Dome you have encountered. After you turn and to follow the Transantarctic Range and head precipitously down towards the west coast, you will encounter more ice domes than you can shake a stick at… Well, mostly you can’t shake a stick at them because there are no sticks to be found. Ice acts just like water, except more slowly (much more slowly) and on your steep descent to the coast you will be doing the ice version of a rapids.

After Hercules, the going should be “easy”; easy only if you can call travel in Antarctica “easy.” Mostly it will just be ice sheet travel until you spot the Pole a little past 2,920 kilometers. And yes, there really is a pole. You are required to turn on the outside of the South Pole. Do not cut the course, by taking the shortcut inside the pole!

From the South Pole (9,300 feet elevation), you will make about a 120 degree turn and head off to meet the Transantarctic Mountains where they curve westward to meet the sea. At this point you are going to start picking up the Katabatic Winds again, but this time they will be at your back. Until you reach the mountains you are in for some of the easiest travel of your trip, as you will be crossing an almost featureless ice sheet for the next 1200 kilometers. Your goal is to hit the Transantarctic range at Mt Markham. The twin peaks of Mt Markham, the highest at 14,272 feet, make a good landmark to shoot for, so that you don’t wander too far into the Transantarctic Range. You want to skirt just outside of the mountains for “better” terrain. Marginally better, but better.

Source: https://adam.antarcticanz.govt.nz/

The Transantarctic Mountains that we have been criss-crossing since we landed has a quite different origin than any of the mountains we have encountered so far. If you recall way back in Regions 1 and 2, the mountains of Central and northern South America were formed (and are still forming) from various collisions following their breaking loose from supercontinent Gondwana. Another defector about 186 million years ago was Australia-Antarctica. It wasn’t until about 80 million years ago that Antarctica broke up with Australia.

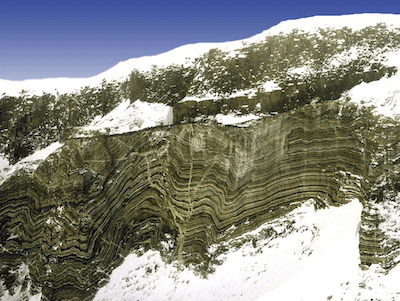

About 40 million years ago, West Antarctica began pulling away from East Antarctica, along the rapidly spreading West Antarctic Rift Zone. Up until now it has been easy to visualize the mountains being formed by the borders of continents colliding, or bulldozing up the seafloor, of one going under another and pushing it up into the air. But how can mountains form along the edge of a continent that is pulling away from the other? To make it even more confusing is the makeup of the mountains themselves. There are layers of normally accreted materials from when the flat continent was far from the pole; great fossil beds from the Jurassic, when Antarctica was attached to all the other continents, and dinosaurs walked where you are walking today.

There are layers of magma speaking of volcanic activity, and tectonic actions. And there are even great chunks of seafloor materials. Theories have been advanced, and at least three of them seem plausible enough to explain these unusually steep and rapidly uplifted mountains. But three mutually exclusive theories cannot all be right… and even leave the possibility that none of them are right. Antarctica hides many mysteries under the ice. But perhaps the greatest mystery of them all is thrust up right in front of our eyes.

Once you get past Mt Markham, you almost have it made. There are less than 1000 kilometers to each the sea, it is almost all downhill, with the wind at your back, and you will be picking your best route through some unique scenery.

Among all the other amazing sights,, now that you are in Victoria Land, are the Antarctic Dry Valleys. Except for having slightly more oxygen, this is as close to being on the surface of Mars as you can come on earth.

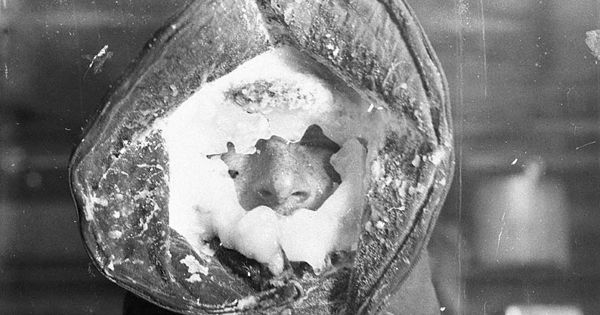

What you are really searching for, once you hit the Dry Valleys is one thing; mummified Weddell Seals. What are you looking for mummified seals? There are hundreds of mummified seals in the Dry Valleys, up to 40 miles from the sea (and elevations up to almost 6,000 feet). No one knows why they are there. No one knows what drove them to travel such a prodigious distance from the sea. No one knows how long they have been accumulating. This is the Antarctic; perhaps for thousands of years. The Antarctic will end with one last mystery for you to ponder. But, it will end. When you see the first seal, you will know you are within 40 miles of the coast. Your Dornier is warming up.

You are headed just outside the Admiralty Mountains, the last of the Transantarctic Ranges to an abandoned Soviet research station called Leningradskaya. You can take such refuge as you can find there until your Dornier arrives. Then you will make the flight to Tasmania, covering the distance that has opened up between there and Antarctica over the past 80 million years. All the paperwork for your border crossing will be taken care of by the CRAW staff on the plane.

We are counting on those of you who reside or have visited these places

to enrich our file of pictures, information, and stories about the places we are visiting. Anything is fair game: Geology, History, unique places to visit, quirky local customs, you name it. We call this part “Boots on the Ground“. Nobody really knows a place better than someone who has their boots on the ground.

If we all share what we know, we can all have quite a journey around this planet. Don’t be shy. If there is one thing I have learned, it is that everyone I meet knows something that I don’t know. Your perspective will make everyone’s trip more enjoyable.

Please share your stories in the comment section below.