CRAW Region #2, Country #10: Peru

After Ecuador was so fascinating, I wondered what would be left to say about Peru. Wouldn’t you know, Peru is even more fasciniating. Peru is the land of great mysteries. I think the place to start in Peru is with part history and part geology (and no real mystery)…. Huaynaputina.

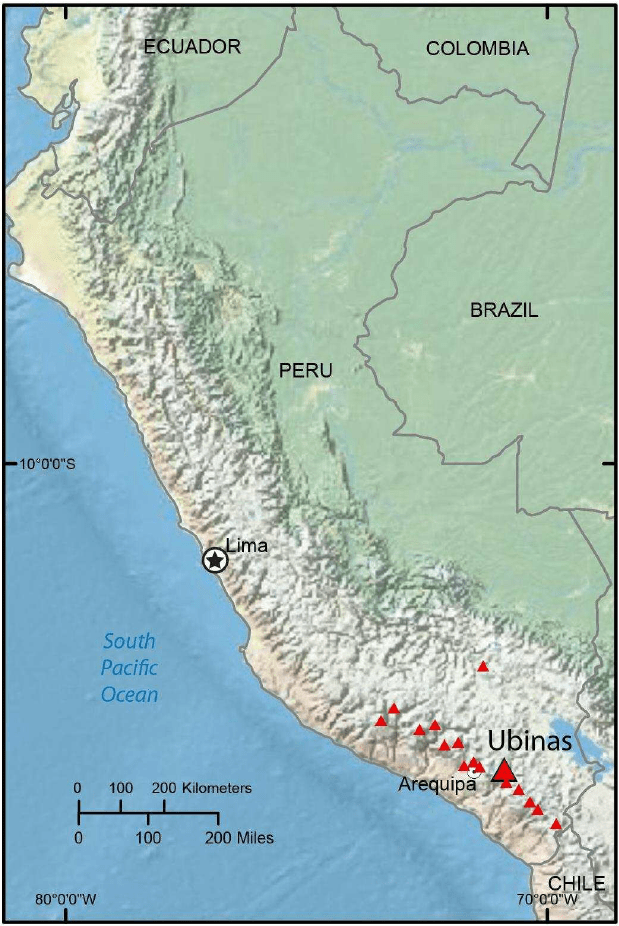

Huaynaputina is one of the many volcanoes in the southern end of Peru. It is not one of the big impressive looking volcanoes. But it might have had the biggest effect on the rest of the world of anything that came from Peru, with the exception of the potato. Huaynaputina is not a big impressive looking volcano, because there is not much left of it besides a two-mile wide crater with some ash domes inside.

On February 15, 1600 a series of earthquakes began in the area surrounding Huaynaputina, at that time a big, impressive looking volcano. Earthquakes continued to come every 5 or 6 minutes, growing in intensity thru the night of February 18, by which time they were powerful enough to shake people out of bed. Between 1100 and 1300 on February 19 two massive quakes struck, destroying almost every structure in the area, causing massive landslides, great deformations on the surface and opening huge cracks in the ground. Needless to say, there was widespread panic by this time, and not without reason. At 1700 hours on February 19th Huayaputina blew up.

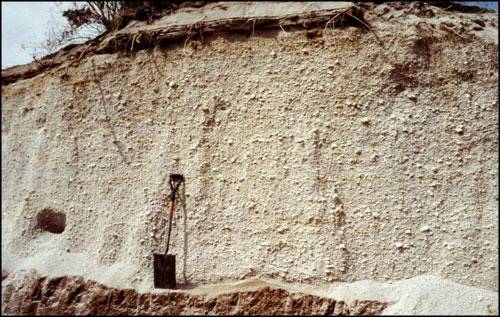

The blast was heard in Lima; 520 miles (837 km) away. Cities 50 miles (75 km) from the volcano were destroyed by the shock wave. The ash plume shot 120,000 feet (35 km) into the stratosphere. Flaming rocks rained down on the surrounding countryside, coming down as far away as Lima, and even being reported by a ship 1,000 kilometers out to sea. Pyroclastic flows shot out in all directions, incinerating villages nearby, and burying Tasanto and Calicanto under more than 10 feet (3 meters) of material. Flows of ash and pyroclastic material reached the Rio Tambo, creating a lahar that roared downstream all the way to the ocean, extinguishing villages along the river with all their inhabitants. And an hour after Huaynaputina vanished, the ash began to fall.

In the aftermath of the blast, 50 square kilometers were buried under deep deposits of ash and rock. Cities were destroyed, or had ceased to exist. Crops and livestock had been totally eradicated, and flows of lava continued to boil out of the ground around the huge wound in the earth. Dust obscured the sky for 9 months after the explosion. The result was the utter ruin of the economy of southern Peru. The destruction was so complete that it took 150 years before the area had fully recovered.

A blast like that today would wreak havoc around the world. And the 1600 eruption had the same effect: “Analysis of tree ring data gathered throughout the Northern Hemisphere indicate that 1601 was, on average, the coldest year out of the last 600. In Switzerland, 1600 and 1601 were among the coldest years between 1525 and 1860. In Estonia, the winter of 1601–1602 was the coldest in a 500-year period. In Latvia, the late date of ice breakup in the harbor at Riga indicates the winter was the worst in the 480 years before today. In Sweden, record amounts of snow in the winter of 1601 were followed in the spring by record floods. In France, the wine production went down and came late that year. Lake Suwa in Japan had it’s earliest freezing in 500 years. The peach trees in China bloomed late. People around the world felt the effects of Huaynaputina’s eruption. Climate at the time could have played a role as well. In 1600, the world was in the midst of the Little Ice Age, typified by harsh winters, springs and summers much cooler and wetter than normal, and shorter-than-average growing seasons. A large volcanic eruption during that period would have depressed average temperatures even further.” Granyia

One last, certainly not coincidental, event was the great famine in Russia, between 1601 and 1603, when nearly 1/3 of the population died of starvation; some two million people.

It is beyond unlikely that the remnants of Huayanputina will erupt again while we are passing directly below. However, there are 20 sister volcanoes crowded around the same area. Thus the clause in your waiver regarding pyroclastic flows, lahars, or flaming rocks falling from the sky.

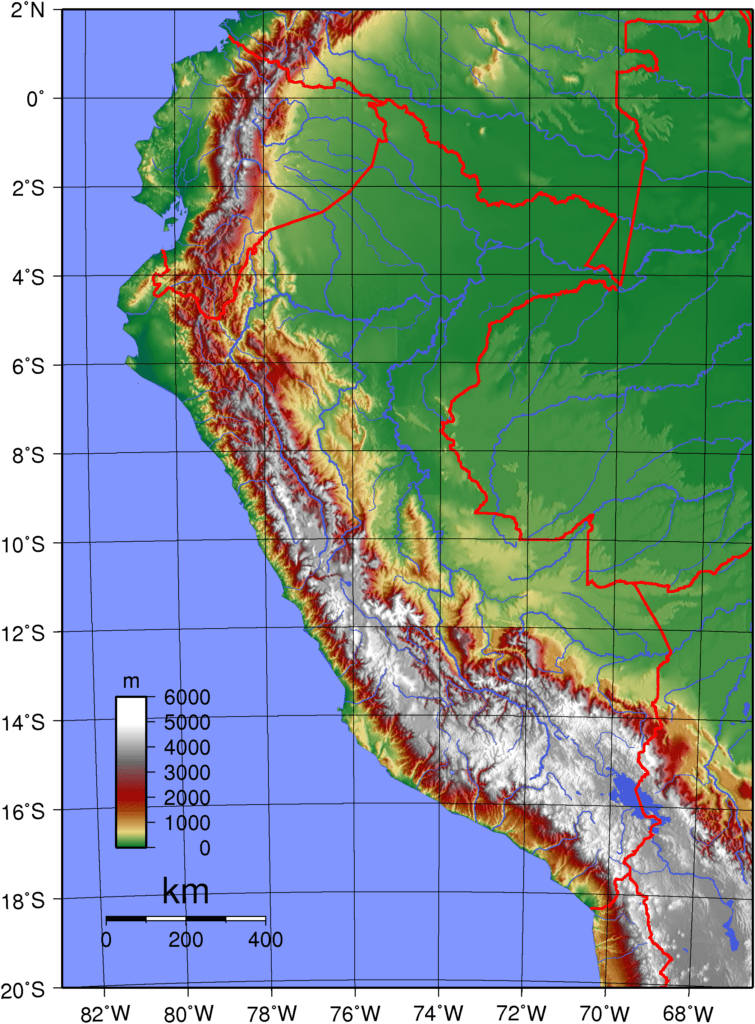

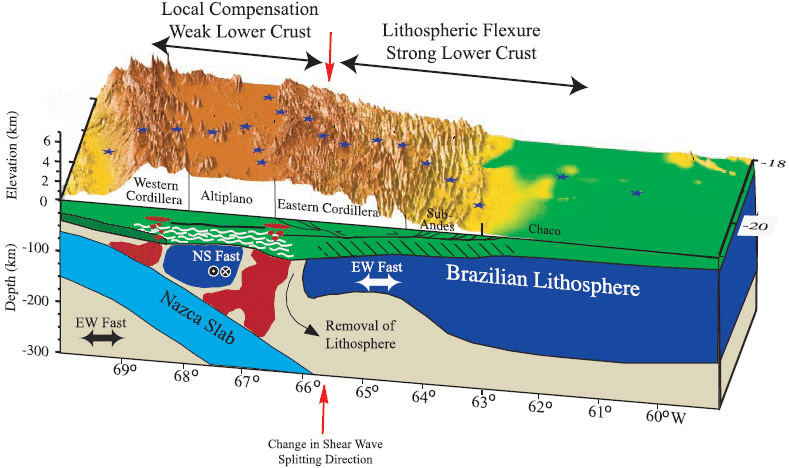

A general description of Peru that we will be running through is coastal plain, with one big loop up into the mountains to take us around Lima. The coastal plain through Peru is a very thin band. Not surprising, since the west coast of South America is constantly being compressed by the Nazca Plate sliding under it, as Nazca moves east and the South American Plate continues to steam westward. The mountains, however, are Peru’s defining feature. At the northern end, near Ecuador and right on the westernmost point of South America, the Andes are in a single chain and are about as low lying as the chain gets. This area is called the Loja Knot, because below this knot the Andes split into, once again, the Oriental and Occidental Cordilleras.

Between the two is a high plateau known as the Altiplano.

The Altiplano is second in size and elevation to the Tibetan Plateau and stretches 600 miles from central Peru across Bolivia into the northern tip of Argentina and Chile.

The actual processes that created this feature are still a subject of conjecture.

Another thing that really surprised me about Peru was its sheer size. There is a grab bag of South American countries: Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay; that we tend to think of as all being the same size (at least in the states). Peru is the largest, with Venezuela a distant second. And Peru is not squarish; it stretches along the Pacific coast. Our trip across Colombia and Ecuador combined was only 2,250 kilometers… Peru will take us 2,740. So be prepared to spend some time here.

I had thought that all the most important Inca facts had been covered in Ecuador, leaving more time to look at other aspects of Peru. But, once you arrive in Peru, the mystery of the Inca only deepens. Maybe the total mystery of Peru deepens. What is it about this place that spurred the rise of civilizations? The earliest humans in Peru, 10,000 to 12,000 BCE populated the narrow coastal areas, and lived to a great extent off the fruit of the sea. Even the first agriculture, 7,000 BCE was oriented towards fishing… gourds for floats and cotton to make nets. By 6,000 BCE the people were moving from the coast up into the river valleys, as maize became a staple crop…. And according to legend, higher up into the mountains the domestication of a small tuber had begun; a tuber that would become one of the world’s most ubiquitous crops.

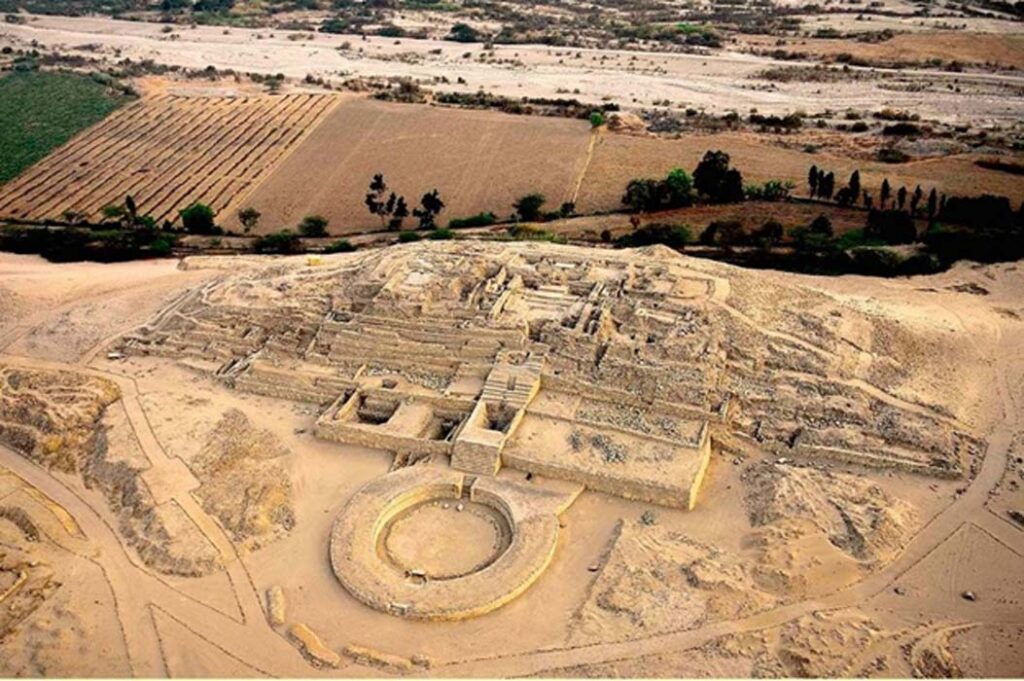

Then in 3500 the Norte Chico civilization came on the scene. The oldest civilization in the Americas, and one of the 6 oldest in the world, the Chico left the remains of large buildings, pyramids, irrigation canals, and mysteries. The greatest mystery is why they abandoned it all in 1800 BC after 1700 years.

Other civilizations followed; the Cupisnique culture from 1500 NC to 1000 BC, the Chavin from 900 BC to 200 BC, the Paracas, Moche, and Nazca. Each contributed to the developing Andean cultural traditions that would come to full flower with the Incas. Irrigation canals, pottery, child sacrifice. Then there was the first inkling of empire. Two great powers developed in the Peruvian area. Tiahuanaco was a city on the Altiplano, on the shores of Lago Titicaca. Where there had previously been many small settlements, those were gradually abandoned, as the population moved to Tiahuanaco. Tiahuanaco grew larger and larger, until its population was around 20,000 in 800 AD… At that time the population of London was around 10-12,000.

Equally as unusual as moving the entire population of a large rural are into a single large city, was the development around that city of what can only be described as corporate farms. Clearly these were for the purpose of feeding the city. But what social structure could have led to such an unusual arrangement for those times?

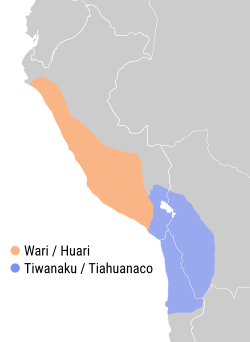

Nothing about the Teahuanaco culture was normal. Another peculiarity was the settlement of “colonies” up to 300 kilometers away. The intervening land was not conquered, but rather large colonies were constructed in other parts of the Altiplano, the Azar Valley in Chile, and in Peru, where they butted right up against the first semi-empire in the Andes.

The Huari Empire. It is not certain exactly how the Huari came to dominate their territory. Religious conversion has been suggested, although military conquest is in the more traditional mold for empire building. Whatever the method, the “subject” cities in the Huari empire retained some autonomy. By 800, the Huari empire had reached its zenith, and went through a period of decline thru about 1000 AD, when the capital city was largely depopulated. Mysteriously, the doorways of the major buildings were blocked before being abandoned. Sort of like locking the doors pending a return… that never came.

The Huari added one more innovation that would reappear in the Incan empire later. They kept their records with khipu, a system of keeping records with knotted ropes. (Peru 17) The year 1000 also marked the end of the enigmatic Teahuanaco civilization. Teahuanaco was abruptly abandoned. Altho there is much damage to the structures, it is uncertain if that was contemporary with the abandonment, or was inflicted later. With Teahunaco gone, it’s colonies soon faded from the scene.

For the next 400 and some odd years, Peru was a land of city-states, that rose and fell, until in 1438 a man named Pachacuti came to power in the minor Kingdom of Cusco setting at over 11,000 feet elevation in the Andes. Pachacuti was the 9th Inca and he set out upon a campaign of conquest that has few rivals in history.

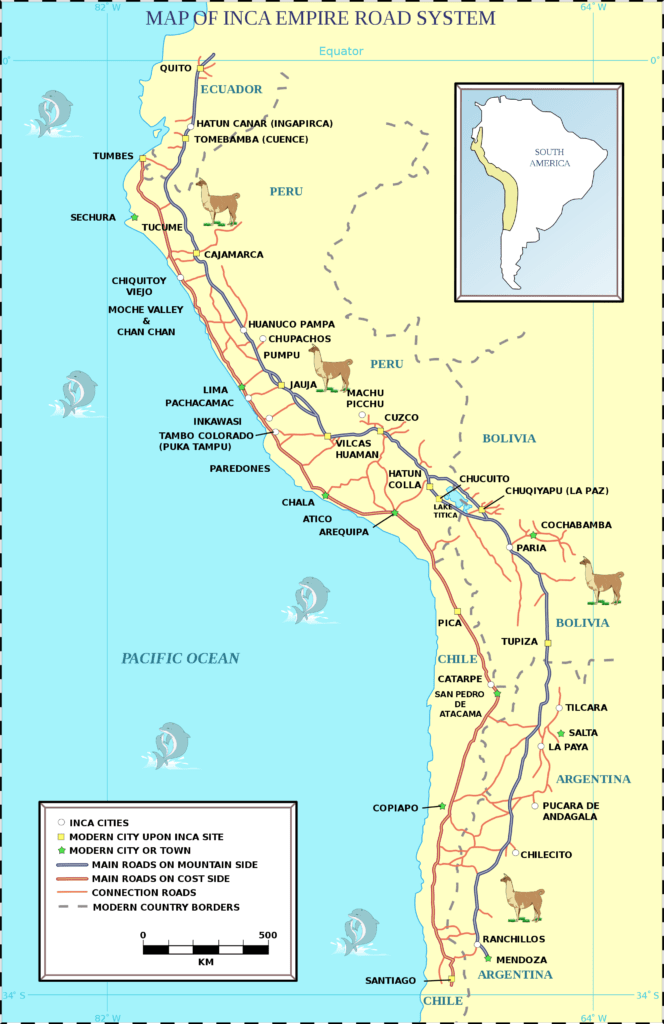

We know a lot of things about the Inca Empire, but what we know only raises more questions than it answers. In less than 100 years, the population of true Cusco Inca numbered at most 30-40,000 individuals. Yet somehow they conquered and administered an Empire of more than 10 million inhabitants, and could field armies that numbered in the hundreds of thousands. They had no monetary system and all trade was done by the barter system; taxes were collected in the form of labour, which allowed them to build a 25,000 mile road system linking all corners of their empire, and undertakes the breathtaking public works projects that draw tourists from all over the world today, even though most of their work was destroyed by the Spanish. Their children were given aptitude tests at an early age, and either trained as craftsmen or prepared to become administrators of the Empire. The Empire itself was divided into 4 parts, defined by their compass direction from Cusco, each with its own governor (the Sapa Inca), and ranks of administrators under him down to the local Yanakuna. These positions were filled by the trained Inca administrators, and were given no choice in being assigned to the foreign service. The concept of wars of conquest in search of riches that spurred the Conquistadors was nonexistent. Everything in the Empire belonged to the emperor. They had no written laws, but made decisions based on tradition. Local nobility retained their position, served alongside the Yanakuna and were called Kurakakuna. Local religion was not interfered with, but the Inca social hierarchy and agricultural practices were imposed on the conquered peoples, and to a great extent persist to this day.

We are left with these few facts about the Inca, but the detail of how this unprecedented empire was built and how it worked is lost. All the records were kept in the form of those invaluable khipu. Perhaps the greatest crime of the Spanish was in the burning of nearly all of those records. How strange, in this country about which we know so many details, that the answers to the big questions will forever be shrouded in mystery.

Your time in Peru starts innocuously enough, running along the coastal plain. Before you leave the country you will have hit points between 15,000 and 16,000 feet five times. But that is all a long way away, when we dip inland, and up into the mountains to avoid the certain death that would be any attempt to pass thru Lima on foot. Your safety is always our first consideration (if you overlook the fact that we did take you through El Salvador)

The land around you is a vast expanse of scrub; dry, rocky and sandy, scrubland. We are crossing the Sechura Desert. The ocean is there, somewhere to the west. But no sign of it exists. The Andes are there, somewhere to the east. But no sign of them exists. For all intents and purposes you are in the middle of a vast desert.

Much of the land seems empty, but there are low hills and dry runoffs to add features. Periodically there are haciendas, to leave you to speculate how someone lives on this barren land. I know a lot of people do not care for desert crossings, but I have always found them enjoyable. There is no real way to appreciate the vast emptiness of these places like passing thru them slowly.

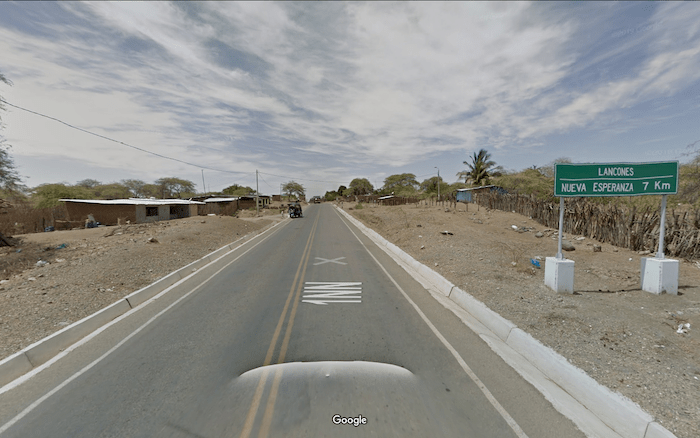

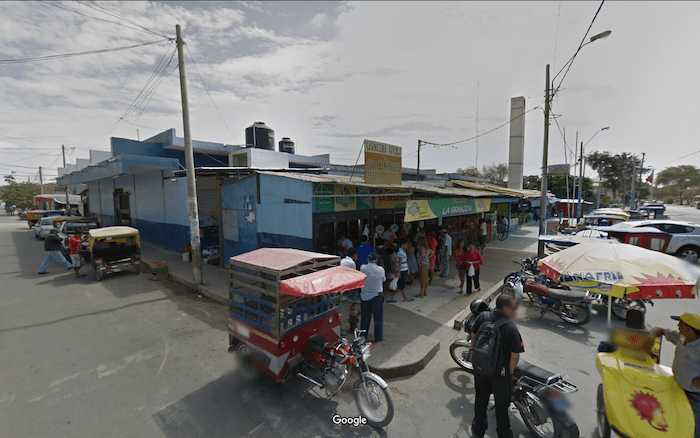

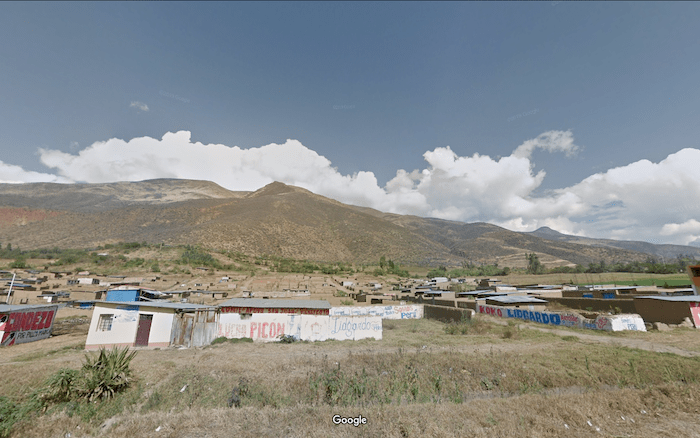

But, the Peruvian desert is not completely empty. Periodically you will pass thru bustling villages like Lancones.

and you will pass dusty roads that lead off into the scrublands… heading to places only your imagination can fill in.

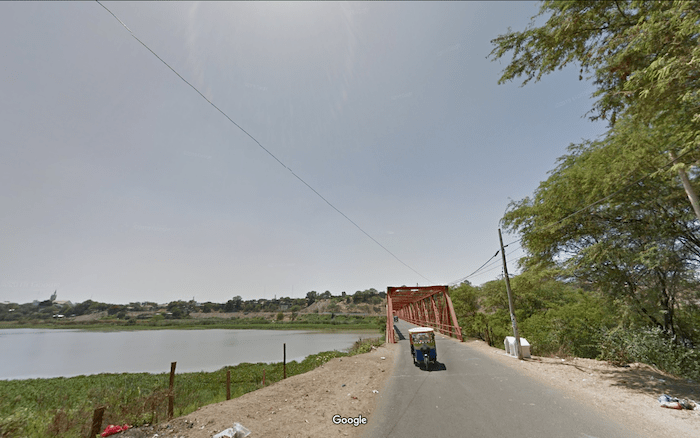

We cannot see the mountains to our east, but they are there. Periodically we get a reminder of the things unseen. Like coming to an oasis of green in the midst of all the brown, when we come to the crossing of Rio Chira at Sullana. Somewhere far from us this begins as snowmelt high in the mountains.

Further into our desert crossing, you will come to Piura, on the Rio Piura. Altho the route technically only brushes the city, we recommend that you turn off and pass thru the center of town. It will only add a few kilometers of distance, and Piura is a city full of sights, with its colonnaded homes and bustling shops. You can have lunch at one of the many small food shops to be found. Piura is a little bit of a tourist destination, since the beach is actually not far away (for those people who travel by car). You won’t probably have time for the beach, but traveling self powered you will get to see the city from a much better vantage point.

After Piura, the scenery becomes even more desolate, as we cross the more than 200 kilometers of nothing between Piura and Chiclayo.

This is the heart of the Sechura Desert. I am not even certain if we were technically in the Sechura when we first crossed the Ecuadorean Border. The entire coast of Peru is a desert, but only the one small part you are currently crossing is called a desert and has a name. When you tell people you crossed Peru, they will only picture rain forests and Inca ruins. But most of our time in Peru, we will be in the desert. However, this is a different kind of desert. More than 40 rivers cross the desert between the Andes and the ocean, and each one is a green oasis. Four of Peru’s five largest cities are in this desert.

Chiclayo is on the Rio Chancay. It may almost become disorienting at some point, this repeated alternation between bustling cities nestled in lush green valleys and the barren emptiness of the desert.

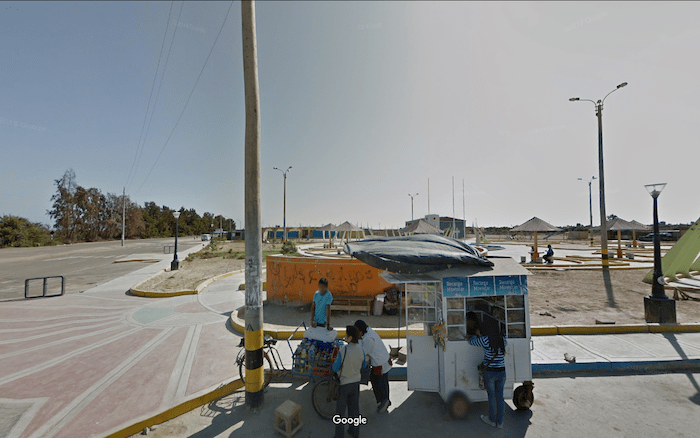

500 kilometers into Peru we reach Tujillo and the Rio Moche. Just across the river is Moche, and our closest approach to the ocean before we start to climb up into the mountains to circle around Lima. From Moche a short side trip will give you a chance to eat on the beach.

Finally, 2840 kilometers into region 2 and 600 kilometers into Peru, we turn off of the Pan American Highway that we have been following since Colombia onto a dirt road and head towards Tanguche on the Rio Santa. There we will turn east and head for the Andes.

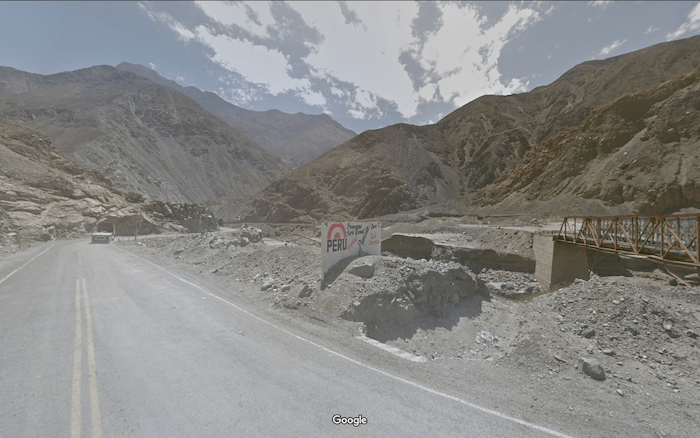

It takes no time to find yourself climbing and climbing. You will pass thru the arid mountains of the Calipuy.

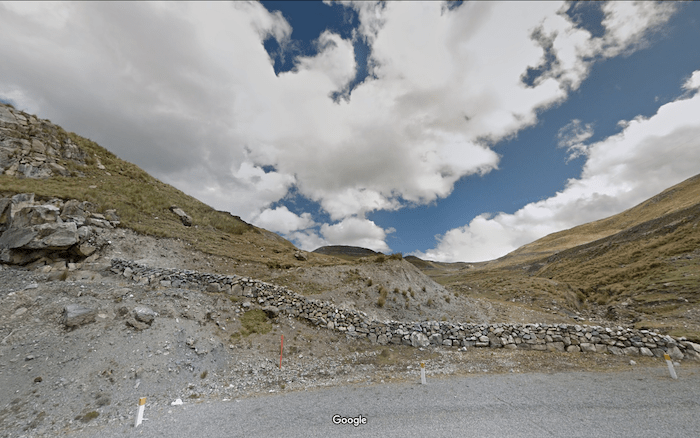

and head up to the top of the first Cordillero at over 10,000 feet, 2960 kilometers into the region, before running at the base of the second for the next 200 kilometers… 200 kilometers of never ending fantastic views at elevation. Then you will turn and climb, and descend, and climb, and descend. 10,000 feet; 15,000 feet; 13,000 feet; 16,000 feet; oxygen is a dim memory from back in the desert by the sea.

3,990 kilometers after we landed in Colombia; 1,150 kilometers after we left the ocean to climb around Lima, we finally arrive in Pisco. We are once again close to the Pacific, and the air probably feels as thick as soup after a thousand kilometers of running or cycling at altitude. We recommend you take a short detour to see the ocean once more.,, because you are about to launch back into the mountains again!

Well, not the high mountains, but back up off the beach. The road near the coast most of the length of Peru is broken between Pisca and Puerto de Lomas. The next place you will reach is the town of Ica.

During our run we may not have seen Inca ruins or rain forests, but we run thru many cities that bear the names of the ancient civilizations that each had their time in Peru. Like the Moche and the Huari… and the Nazca, who also gave their name to the Tectonic plate that is building the Andes.

Returning to the coast at Puerto Lomas (4300 kilometers) you still have another 700 kilometers to reach the Chilean border. You will hug the coastline the rest of the way. Enjoy the cool seas breezes and the scenery!

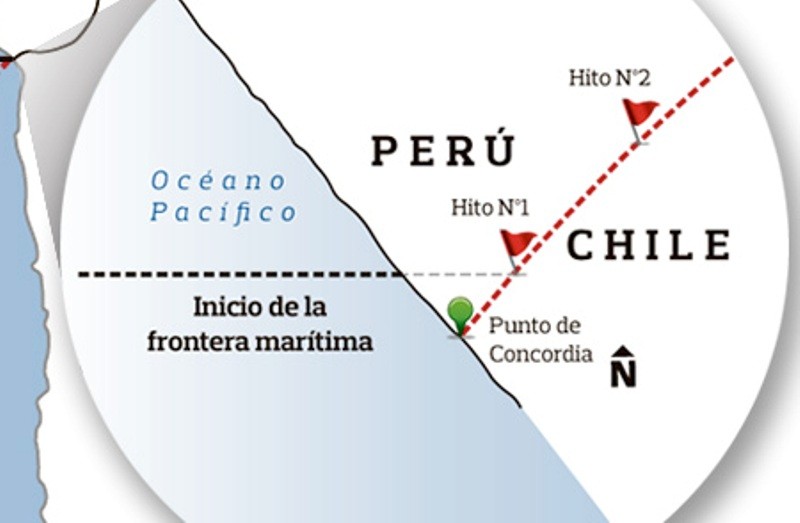

Hopefully you will reach the border in Los Palos during a peaceful time. Chile and Peru have been having an off and on border war for the past 130 years over 10 acres of land on the coast. As if they neither one have quite enough sand.

Crossing the Border from Peru to Chile at Los Palos

This one can be dicey. So few people cross here that the procedures might be different for every CRAWdad that completes the 4,990 kilometers of Region 2. However, assuming they are not shooting at each other, the Chilean and Peruvian Immigration are in the same place, so you will be able to get your exit stamp, and then submit to an extensive search for fruits or vegetables. Did you not pay attention when we advised you to eat in Los Palos before crossing? If you did not attempt to smuggle food into Chile, you should soon be on your way into Region 3, and an entirely new set of adventures!

We are counting on those of you who reside or have visited these places

to enrich our file of pictures, information, and stories about the places we are visiting. Anything is fair game: Geology, History, unique places to visit, quirky local customs, you name it. We call this part “Boots on the Ground“. Nobody really knows a place better than someone who has their boots on the ground.

If we all share what we know, we can all have quite a journey around this planet. Don’t be shy. If there is one thing I have learned, it is that everyone I meet knows something that I don’t know. Your perspective will make everyone’s trip more enjoyable.

Please share your stories in the comment section below.

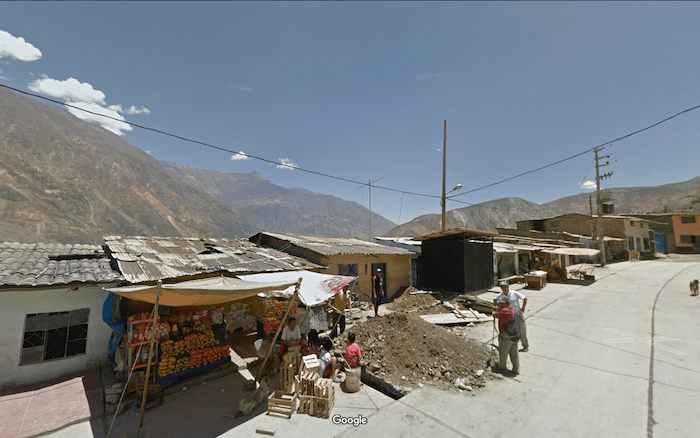

Laz has you traveling down the coast of Peru so I will add a few pictures from deep in the Andes and from the Amazonian lowlands of Peru.

The photo below is of me and a fellow bird watcher and runner who lives in Peru. The road we are on goes to Inferno. And it felt like it, very hot and very humid

A general store on the banks of the Rio Heath, the border between Peru and Bolivia

Rio Heath, border between Peru and Bolivia

A view of the Rio Madre de Dios as it leaves the eastern foothills of the Andes and enters the Amazonian lowlands

Incan stonework. No mortar is used.

Path across the small area of Peru that is classified as Pampa. It was flooded with about 8 inches of water. Great training run.

This picture is of a series of tunnels on the road we traveled that ran north/south through the center of the Andes. Very dry in this area.

This picture is Mount Huascaran, the highest point in Peru and the second highest in the Andes.

Burial structures built by the Colla, a pre-Incan civilization that lived in the altiplano.

Golden-backed Mountain-Tanager. A highly sought after bird species that takes a good hike to reach.

Laz has you traveling down the coast of Peru so I will add a few pictures from deep in the Andes and from the Amazonian lowlands of Peru.