CRAW Region #2, Country #9: Ecuador

Having passed easily through the almost cursory border crossing procedures, you are ready to begin your journey through Ecuador. Prepare to travel through one of the most biologically diverse nations on earth. The good news is that the human threat is pretty moderate by comparison to most of your journey so far. But you can expect the minor inconveniences of flash floods, tsunamis, earthquakes, and volcanoes. But nature isn’t all threat in Ecuador. You have reached the climatic paradise, where temperatures vary by about one degree Celsius from midwinter to midsummer.

Even tho the three Andean Cordilleros in Colombia attach to the top of the single cordillero of Andes that runs the length of South America at the border with Ecuador, they were neither formed at the same time, nor in the same way. The Ecuadorean border marks the beginning of the “new” true Andes. South America steamed across the ocean unobstructed for about 100 million years, until about 45 million years ago it encountered the Nazca Plate of the Pacific in a head on collision. The Nazca is sliding under the South American Plate, forcing what was once a continental shelf up into the air. This collision first began at the Peru/Ecuador end of the continent, and then slowly engaged all the way down to southern Chile. The last part of the continent is similarly colliding with the Antarctic Plate. The heat created by this grinding process sends molten magma up through fissures in the rock to feed about 150 or 160 active volcanoes along the Andes.

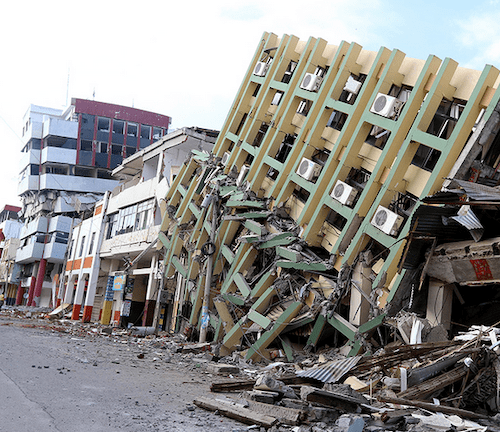

During your trip thru Ecuador there will be a high risk of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

Small quakes occur on average about 2 out of every 3 days. Larger ones are less frequent. Over the past 40 years, there have been 6 quakes between 7.1 and 8.2.

Needless to say, there is also a high tsunami risk while you are near the coast. Be sure that you are aware of the evacuation routes during your trip. In the higher country it is volcanic eruptions, with the attendant risks of lahars, pyroclastic flows, or the release of toxic gasses and ashfall. Be sure you are aware of the evacuation routes during your trip. If you are forced off course by a volcanic eruption, earthquake, or tsunami, you are allowed to rejoin the course at the nearest safe intersection, rather than being required to return to the place you were forced to evacuate. The real mystery is what kind of activity might eventually happen. The Andes, as it turns out, are not rising slowly, inch by inch. The geological record shows the plates underlying the Andes sticking in place, until there is a huge slippage, and the mountains lurch upward. The coast of Ecuador has been compressing at about 1.3 inches a year… for who knows how long. Don’t Dawdle in Region 2, you do not want to be there when it lets go. The Richter Scale might not measure that one.

I saw the question asked; “Who discovered Ecuador?” And I had to laugh at the concept. As if Ecuador was just sitting there on the side of South America, a country waiting to be discovered. Ecuador is like most countries. It is not one place it is a collection of very different places. It is the coast. It is the highlands. And it is the mountains. Countries are not formed by natural boundaries, or homogenous populations. They are a collection of people and places under a single administrative power, which is able to both hold its populations together and exclude the control of any competing administrative power. The last time the people of the place we call Ecuador today were self ruled within a natural geographic boundary was when it was occupied by hunter gatherers.

However, the onset of civilization followed its natural course. In a land like that which is today Ecuador, essentially lacking seasons, the people gradually improved their technologies, developed agriculture, put down roots with permanent homes. Cultures developed, flourished, and were then replaced by more advanced cultures. Villages became cities, and cities formed confederations.

Two primary centers developed and the two cities that remain the two primary cities in Ecuador today became the centers of those cultures. Guayaquil on the banks of Rio Guaya, where it empties into the Gulf of Guayaquil, became the center of cultures that used the resources of the ocean and the narrow coast. Quito, sitting at 9,000 feet in the foothills of the Andes was the center of the cultures that lived off the richness of the highlands.

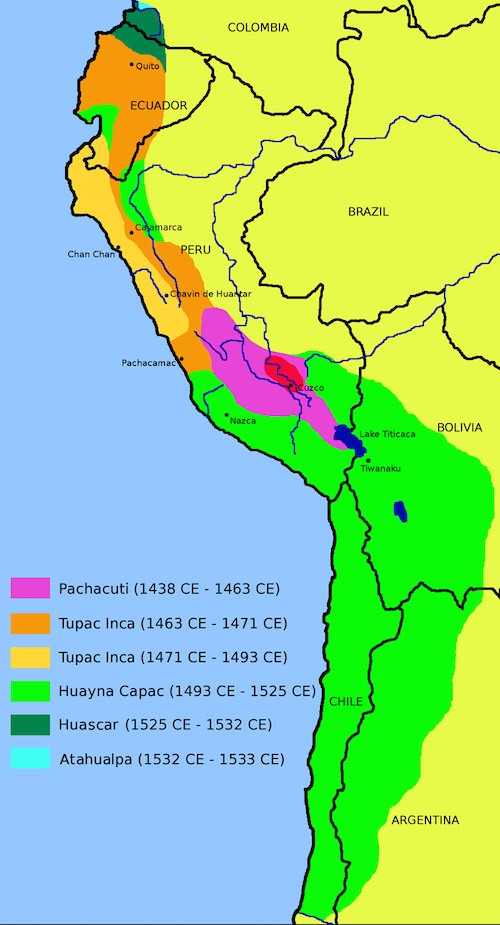

As you certainly expect at this point, the indigenous peoples fell victim to colonization by an avaricious invading foreign power. Now, here is where you expect me to say; “the Spanish.” However, it was not the Spanish at all. It was around 1450, and the Spanish were as yet unaware of the existence of the New World. The Confederation of the Matenos that centered on Guayaquil, and traded up and down the coast as far as western Mexico to the north and Chile to the south, and the kingdom of Quito were conquered and colonized by the Inca.

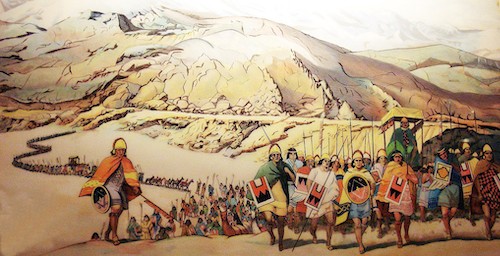

The conquest began in 1463, under the 9th Inca; Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. His son Tupa Ayar Manco led a 200,000 man Inca army into Ecuador, encountering fierce resistance from the tribes that lived along the frontier, who had formed alliances to resist the advancing Inca, as well as the major powers that lived behind them. It was Pachacuti that turned the Inca state from a small tribe that occupied the valley of Cuzco into a power that could compete with, and eventually displace the Chimu. Eventually he built Cuzco from a village into a cosmopolitan capital city, and the Inca into an empire that ruled over all of western South America.

Tupa’s son Huayna Capac completed the conquest of Ecuador and was so enraptured with Quito that he made it the second capital of the Inca Empire, and lived out his life there. The Incas were true colonizers as they took over South America, moving colonists to conquered territories. Unlike the treasure hunters of the Spanish, or the colonists driven by a search to set up a place where their religion could do the persecuting instead of being on the receiving end, or those seeking an escape from economic hardship, the Inca colonists were moved by force. The Inca also built roads and terraced fields, bringing the Inca social structure with them, forever altering the agriculture and social structure of the lands they conquered. Of course we use the term Inca in the Spanish sense, indicating all members of the Inca Empire. In the Inca world, the Inca were the ruling class, consisting of only between 15,000 and 40,000 individuals. They ruled over more than 10 million subject peoples in a social system very similar to feudalism. They had no system of money. Exchange was entirely barter, and taxes were collected in labour. All of the land was considered to be the property of the Incan Emperor, who allowed its use in exchange for taxes.

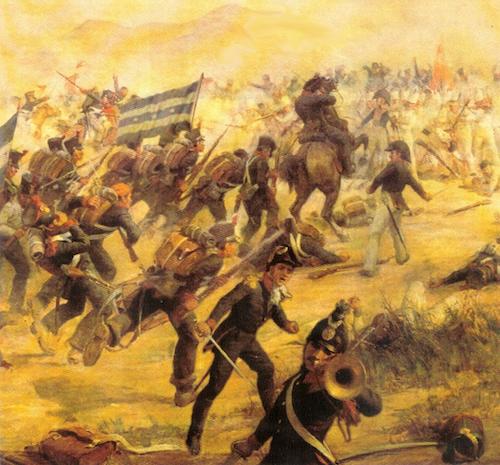

Huayna died in 1527, and a few days later his heir also died of smallpox, which had arrived in the Inca Empire ahead of the Spanish. The legitimate next in succession was Huascar Inca from Cuzco, however he was challenged for the throne by Atahualpa of Quito and a bloody civil war ensued. The key battle of the war was fought in Ecuador near Riobamba, with Atahualpa winning, and pursuing Huascar’s armies into Peru, where Huascar was defeated again in the battles of Chimborazo and Quipaipan in 1532, finally taking Huascar prisoner.

Meanwhile, in 1531 Pizzaro had arrived in Guayaquil, to find an Inca Empire depleted by 5 years of bloody civil war, reeling from the raging smallpox epidemic, and bitterly divided still between the followers of Atahualpa and those of Huascar. A year later, after the conclusion of the Inca civil war, Pizzaro, closely followed by other Spanish opportunists set out on a conquest of the Empire, the outcome of which was almost preordained by the circumstances.

From 1544 until 1720 Ecuador was part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru. Spanish were given large land grants called encomienda, on which, surprise, the indigenous people were used as slaves. By 1589 there were 500 encomienda, however, the president of the Audienca stopped granting encomienda, as the recipients were just selling them. Still, the existing system continued until nearly the end of the colonial period.

The Ecuadorian economy, as with most of the Spanish Empire, went through a depression through most of the 1700’s, which eventually reduced most of the encomienda owners to poverty. The indigenous people actually were better off, as many were released to return to their traditional communal farming way of life.

The big break for Ecuador happened in 1720, when the Viceroyalty of New Granada was formed, based in Bogota, Colombia. Ecuador was removed from the Viceroyalty of Peru and Thrown in with New Granada, and Quito was given its own Audiencia. While under the central control of New Granada, for the first time The lands that would become Ecuador had its own administration.

This is where a common theme comes up in the history of every country in both regions so far. 1820. This is a good place to talk about the resentment between the Criollos and the Peninsulares that underlay these revolutions. The Criollos were people of pure Spanish heritage who were born in the new world. The Peninsulares were Spanish born residents, and enjoyed many privileges under the law. It was a natural thing that this led to a lot of resentment; however both groups remained loyal to Spain. The turning point came in 1808 when Napoleon took over Spain, deposed Ferdinand and installed a Frenchman, his brother Joseph, as king. This led to a fomenting rebellion among the Criollos in Quito, with enough momentum building to declare independence, and seize power from the Spanish government…. Ironically as an expression of loyalty to the Spanish King.

When a Spanish army was sent to squash the rebellion, the Criollos found that there was not enough popular support to mount any resistance. So the revolutionaries peacefully surrendered to the Spanish forces with a promise of no reprisals. However, the returning Spanish authorities instead began a purge of the rebels, sweeping up many innocent supporters in their wide net. Reprisal accomplished what the rebel leaders had not, building enough resentment and popular support to create a real rebellion, and after several days of street fighting the Spanish forces were driven out of Quito. A majority Criollos junta was formed, with a Peninsular as its head. They wrote up a constitution declaring themselves independent of the current Spanish government, with the clause that they would recognize Spanish authority if Ferdinand was returned to the throne.

Flush with victory, the Quitinos formed an army in 1811, and marched off to confront the Spanish forces in Peru. Ill trained and poorly equipped, they were no match for a real army, and the Quito rebellion was crushed in 1812. Thus, after a comedy of errors, Ecuador became one of the first Spanish colonies to rebel, thanks to the poor judgment of the Spanish government and had that rebellion fail, thanks to the poor judgment of the rebels.

One rebellion was quashed, but the tides of history were running out on Spain. By the year 1820 calls for independence were heard the length and breadth of Spain’s American Empire, while Spain itself was a faltering power. Real armies had formed to throw of the yoke of Spain; Simon Bolivar led one in the north, and Argentine Jose de San Martin led one in the south. There were allies available to support a revolt. This time the rebellion began in Guayaquil. Rather than face Spanish forces with a makeshift force, Gran Colombian and Argentina sent experienced troops, and Bolivar dispatched General Antonio Jose de Sucre to lead the force. And when the rebel army ran into trouble, San Martin sent additional troops to turn the tide.

Freedom did not rest easily on what was to become Ecuador, still called the Audiencia of Quito. Bolivar and San Martin met at the Conference of Guayaquil to decide how to divide the newly freed lands. Guayaquil and Quito were nearly split up, with Guayaquil going to Peru and Quito to Gran Colombia, a move that would have altered today’s world map significantly. However, Quito remained intact, and was joined to Gran Colombia.

Unfortunately, a successful end to the rebellion did not bring peace to Quito. First it was caught up in the center of the war between Spain and Gran Colombia, as Gran Colombia fought to secure Peruvian independence. And, when that war was ultimately successful, a grateful Peru promptly went to war with Gran Colombia over the locations of Peru’s northern border. Quito was again caught in the middle. After more years of warfare, the border was ultimately established where? Exactly where it had been under Spanish rule.

In 1830, Gran Colombia called a Constitutional Congress to develop a constitution for the new nation, which ended instead with Venezuela and Quito seceding, and Quito called its own Constituent Assemble and drew up a constitution, naming the new nation Ecuador. The odd marriage of coastal Guayaquil and highland Quito seemed to have been forged into a solid union by wars that seemed to serve little other purpose, and Ecuador had finally been discovered.

Ecuadorean history from 1830 to now is simply too convoluted to attempt to detail here. Revolts, coups, dictatorships, and spasms of democracy. Instability and seemingly pointless conflict would fill the pages of a thousand history books. It might be unexpected, here in a land cobbled together by the unlikely marriage of two dissimilar cities, where the last extended period of stability ended with the death of the Inca emperor Huayna in 1527, but you will find that Ecuadoreans have a fierce national pride… and one of the most naturally blessed landscapes on earth. And your tour will take you through it all, from the Andes to the ocean. Get ready for some fun!

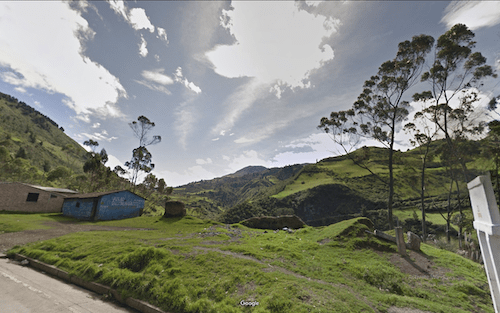

Departing the border you will head directly into the town of Tulcan on the old main road, Avenue Bolivar

Then we head out of town into the high country on a back road that takes us 40 kilometers through the Reserva Ecologica El Angel, where you might not be sure you are on the planet earth, on the way to El Angel itself at 1410 km.

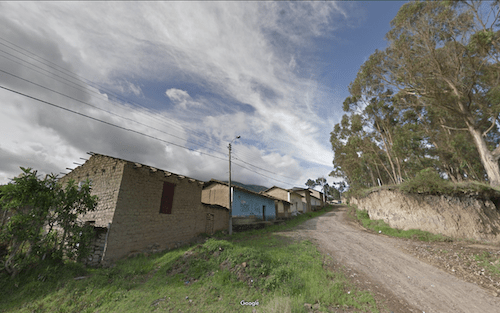

The next 100 miles (160 km) to Quito is an out of this world experience; winding your way through the mountains of north Ecuador, on and off the main road, surrounded by the endless mountains, steep climbs and descents, reaching altitudes of nearly 13,000 feet. Picturesque villages, raw, barren countryside, with a vast blue sky overhead. It is like running in a land created in your dreams.

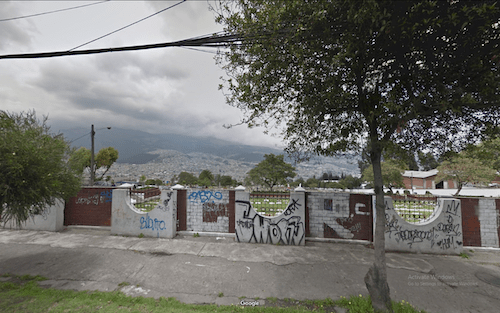

Dropping down out of the mountains to Quito, at 9300 feet is a chance to catch your wind, before heading back up into thin air.

Crossing the high country south of Quito, the skyline is dominated for many miles (and even more kilometers) by the massive, looming cone of Volcan Cotopaxi, the world’s highest active volcano, at 19,347 feet.

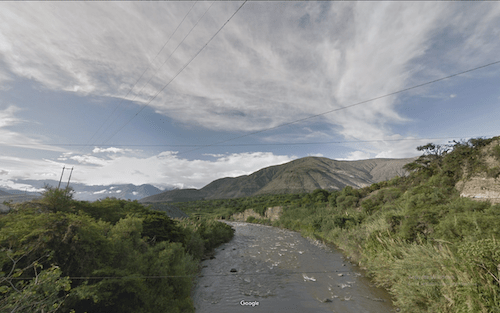

Leaving Cotopaxi behind you find yourself running down the Rio Bamba valley, and past the city of Riobamba. On these very fields the armies of Atahualpa and Huascar battled for control of the Inca Empire, with Atahualpa’s victory still a point of Ecuadorean pride. (Ecuador 13) 1760 kilometers into Region 2, you are still running at 9,000 feet, although the descent to the ocean is growing closer with every stride or pedal. The descent is not immediate, as you climb over 1500 feet to 10,560 Cajabamba over the next 30 kilometers, before plunging 9,500 feet on the old road to Cumanda over the next 80 kilometers.

Down in the Pacific coastal plain, just south of Guayaquil, you get to continue the mix of old roads and main roads as you make your way along the coast.

Finally, after 2240 kilometers of Region 2, you will reach the Border between Lalamor Ecuador and El Alamor Peru.

How to get across the Ecuador-Peru Border at Lalamor

This is the best border crossing so far. Very lightly used. The Aduana on the Ecuador side is a canopy tent. You will have to fill out an exit form. Turn in the form and get your stamp then cross the bridge and head to the Aduana for Peru. You will have to fill out an entry form and get your stamp to enter. If you are scruffy looking (and what CRAWdad is not scruffy looking by now) you might have to prove financial capacity. Be sure to ask for the maximum number of days, as Peru is a very long country, and while you are at about 75 feet elevation at the border, you will climb to as much as 16,000 feet during your crossing.

We are counting on those of you who reside or have visited these places

to enrich our file of pictures, information, and stories about the places we are visiting. Anything is fair game: Geology, History, unique places to visit, quirky local customs, you name it. We call this part “Boots on the Ground“. Nobody really knows a place better than someone who has their boots on the ground.

If we all share what we know, we can all have quite a journey around this planet. Don’t be shy. If there is one thing I have learned, it is that everyone I meet knows something that I don’t know. Your perspective will make everyone’s trip more enjoyable.

Please share your stories in the comment section below.